This practical guide explains the most impactful errors beginners face and the proven, professional ways to prevent them in your first year.

Foxhound Bee Company and industry names like Dadant and Mann Lake note that even experienced keepers lose colonies. Bees are living animals and a hive can change fast, so calm, methodical care matters.

We focus on actions that protect your colony, equipment, and time. Choose standard hives, consult local beekeepers, and plan routine inspections every 7–10 days to limit stress on the colony.

Suit up, learn to use a smoker correctly, and track observations. Harvesting honey can wait in year one; most colonies need their stores for winter.

Key Takeaways

- Use standard equipment and local advice to improve hive survival.

- Schedule regular inspections and keep simple records to spot issues early.

- Dress properly and use a smoker to reduce stings and colony stress.

- Delay honey harvest in the first year so the colony can build stores.

- Learn to read frames and brood to catch small problems quickly.

- Follow guidance from brands and veterans like Dadant, Mann Lake, and Foxhound Bee Company.

Understanding the first year: expectations, time, and local conditions

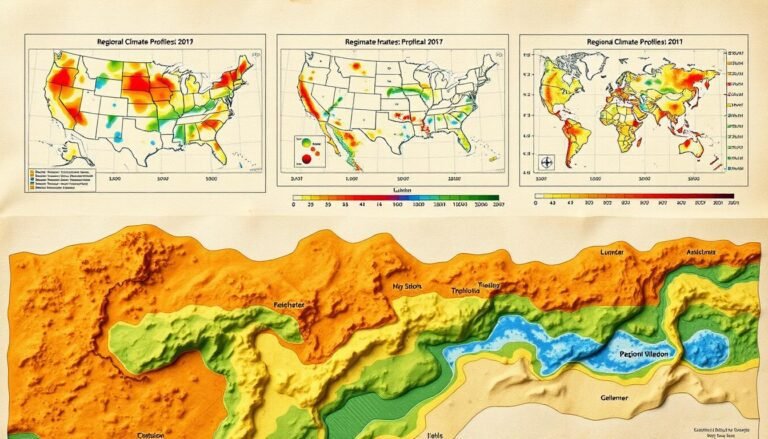

How your bees fare in year one depends more on regional conditions than general advice. Foxhound stresses that management shifts by region and sometimes within a single state. Local weather, nectar flows, and forage diversity set the pace for colony growth and resource needs.

Why beekeeping is local: climate, forage, and timing in the United States

Long winters in the Upper Midwest delay spring build‑up. In the Southeast, earlier springs speed activity and require different feeding and supering schedules. Rainfall patterns and bloom variety define when colonies find nectar and when resources tighten.

How much time to plan for inspections and prep

Block routine windows every 1–2 weeks in spring for inspections. Allow extra time at season start to assemble equipment, fit frame foundation, and stage preventive tasks so inspections aren’t held up by missing parts.

- Choose a calm day with low wind to open a hive and reduce stress on bees and the handler.

- Place hives in full sun on a stable stand with room to work, following Dadant’s advice.

- Keep a seasonal calendar to align work with local bloom and forage availability.

| Area | Typical spring timing | Action to plan |

|---|---|---|

| Upper Midwest | Late spring | Delay feeding, later supering, plan winter stores |

| Southeast | Early spring | Add boxes earlier, monitor nectar flows closely |

| Pacific Northwest | Variable, wet springs | Ensure stands dry quickly, choose sunny spots |

Top mistakes new beekeepers make

Clear, actionable lists turn vague worries into precise, timely responses. A listicle frames recurring errors so a keeper can spot a problem fast and apply a direct fix.

How listicles help you turn common problems into simple fixes

Foxhound and Mann Lake both note recurring themes: DIY gear too early, using non‑standard boxes without local support, and inspecting too often. These habits stress bees and the hive.

- Organizes frequent faults into short steps so beekeepers can act quickly.

- Pairs each error with a simple task: standard equipment, note taking, egg checks.

- Focuses on fundamentals: suit up, proper smoker use, consistent inspections, and reading frames.

| Common Issue | Why it harms bees | Quick fix |

|---|---|---|

| DIY equipment too soon | Poor fit, extra gaps, robbing risk | Start with standard boxes, buy later |

| Over‑inspecting | Stress, missed queen signs | Inspect on a set cadence and note eggs |

| Ignoring local advice | Wrong timing for feeds and boxes | Join a local club and follow regional guides |

Adopt a checklist mindset to reduce anxiety and avoid costly delays. For more on scaling care and timing, see beekeeping expansion tips.

Skipping safety: not suiting up and misusing smoke

Before you lift a frame, make sure your equipment and smoker are set to reduce risk and stress. Dadant advises every beekeeper to suit up for inspections and to use smoke on each opening.

Essential protective equipment for beginners

Must-have gear includes a veil or full suit, gloves, sturdy boots, and a well‑fitting jacket that keeps bees out while allowing dexterity. Proper clothing reduces swelling from multiple stings and helps the beekeeper stay calm.

How to light, manage, and apply smoke the right way

Use natural fuels and aim for cool, dense smoke. Keep a steady burn and avoid hot, sharp puffs that will irritate the colony.

Apply a few gentle puffs at the entrance, under the cover, then over the top bars. Wait a short while before opening for the smoke to mask alarm pheromones and prompt honey feeding.

Reducing stings and stress while opening the hive

Work at midday in good weather when many foragers are out. Move with a calm, deliberate pace to spend less time with frames exposed.

“Smoke prompts bees to gorge on honey and blocks alarm signals, reducing coordinated defensive behavior.”

Keep water or a small extinguisher nearby and fully douse embers when you finish. Practice lighting the smoker at home so it runs reliably when you are inspecting for real.

Opening the hive too often or not enough

Finding the right inspection rhythm protects colony health and saves time for the beekeeper. Openings that are too frequent stress the bees and slow colony build‑up. Long gaps let small problems, like queenlessness or pests, grow unnoticed.

Recommended inspection cadence in spring and summer

Mann Lake recommends opening a hive every 7–10 days during strong spring build‑up. Dadant supports a looser cadence of every 2–4 weeks depending on local conditions. Aim for the tighter window when brood is expanding fast; use longer intervals once the colony stabilizes.

Efficient inspection flow: frames, brood, eggs, and activity

Pick a consistent day and time with mild weather and steady foraging. Light smoke, lift covers, and assess the top box first.

- Work frame by frame, checking for eggs, young brood, and a solid brood pattern.

- Quickly scan stores, drawn comb, queen cells, and signs of pests or congestion.

- Note entrance activity to read foraging strength without extra handling.

- Return frames in the same order and orientation to preserve bee space.

| Situation | Cadence | Key focus |

|---|---|---|

| Spring build‑up | Every 7–10 days | Eggs, brood pattern, supers and space |

| Steady summer | Every 2–4 weeks | Stores, pests, queen performance |

| After interventions | Check in 1 week | Healing, queen acceptance, stress signs |

Use a short checklist so you don’t reopen the hive for missed tasks. Preparation and pacing protect productivity; proper timing and efficient inspections keep hives healthy and responsive. For seasonally organized tasks, see the seasonal checklist.

Not doing your research before getting bees

Investing time to learn placement, equipment, and biology reduces costly surprises. Foxhound urges study first and notes a master guide series that frames practical steps. Dadant also recommends classes, talking to suppliers, and learning equipment basics before you buy.

Books, classes, and reputable resources to start strong

Start with foundational books and hands‑on classes from clubs or supplier learning centers. Good resources pair modern practice with regional advice so your work matches local forage and weather.

Learning bee biology, brood patterns, and correct terminology

Study castes, how eggs develop into capped brood, and simple frame reading. Clear terms help you ask precise questions about a colony or honey stores when you consult mentors.

- Build a pre‑season study plan covering placement, box parts, and seasonal tasks.

- Practice assembling frames and boxes at home to save time at the apiary.

- Keep brief notes from day one to track what works and record advice.

Shortcuts cost more later. If you want structured training, consider Dadant’s recommendations and local classes as the first step.

Trying to incorporate every beekeeper’s opinion

Sorting useful counsel from loud opinion protects your colony from needless change.

Beekeeping includes many valid methods. Trying to combine all input often creates conflicting steps and confused bees.

Foxhound notes that many club members have 0–3 years of experience and that the most vocal are not always the most seasoned. Online forums can leave out local context and important details, which hides the real problem.

“One clear, local voice is worth more than a dozen loud but untested opinions.”

Choose one or two trusted mentors whose outcomes match your goals and region. Test one change at a time per hive to see what works.

- Weight advice by local results, not volume.

- Document counsel and compare it against your inspection notes.

- Make decisions that serve your hive, not debates without data.

| Source | Strength | How to use it |

|---|---|---|

| Local club mentor | High (regional experience) | Follow proven schedules; ask for hands‑on demos |

| Social media | Variable | Verify context; avoid instant changes |

| Supplier guides (Dadant, Mann Lake) | Reliable | Use as baseline; adapt by region |

Be patient. Consistent, measured changes reduce stress and help your bees build steadily. Your role as the beekeeper is to filter guidance through local context and your own records.

Keeping bees based only on your own opinion without local advice

Connecting with a local club quickly replaces guesswork with season‑tested guidance. Foxhound notes most counties host monthly meetings and statewide gatherings where members share regional practice on how much honey to leave for winter.

Finding and using your local beekeeping club

Dadant and Foxhound both stress community support for placement, timing, and practical tasks. A club condenses decades of area experience into clear, actionable advice that saves time and costly trial and error.

- Search county extension sites, state beekeeping associations, or ask at supplier stores to locate a nearby club.

- Bring short notes and clear photos of your hive to meetings for targeted feedback.

- Attend field days to compare colonies and learn seasonal benchmarks like winter stores and when to add supers.

- Pair with a mentor for on‑site help during your first season to improve timing and confidence.

Bonus: meetings often share alerts on local pests and forage shifts that protect colonies proactively. A brief call or visit early in the season can prevent a misstep that takes weeks to correct.

“One local observation will often trump a dozen online opinions when it comes to timing and harvest goals.”

Using non‑traditional equipment without support

Choosing an unfamiliar hive style often creates supply and mentorship gaps that slow fixes when a colony needs attention.

Why non‑standard gear complicates help: fewer local mentors know alternative builds and spare parts—especially frames—are harder to source quickly. That delay can cost time and stress the bees when you need to swap a frame or add space fast.

Langstroth boxes simplify learning. Standard frames fit most racks and are easy to replace. A Horizontal Langstroth gives some alternate flow while keeping standard frames available for quick repairs and shared advice.

Practical gains from consistent equipment: inspections move faster, records align across hives, and experienced keepers can jump in when you call for help. Buying or building special frames may push back interventions and waste valuable time.

- Start with one Langstroth hive to learn inspections and brood patterns.

- If you favor alternatives, keep at least one standard rig for emergencies and training.

| Feature | Standard Langstroth | Non‑traditional styles |

|---|---|---|

| Frame availability | High — widely stocked | Low — often custom or rare |

| Local support | High — many mentors use it | Variable — few local experts |

| Repair time | Fast — swap parts quickly | Slow — may require custom work |

| Learning curve | Gentle — standardized inspections | Steeper — unique handling and records |

Match equipment to your goals. Reliable, supported gear gives colonies the best chance to thrive while you learn. For reading and resources that help build core skills, see beekeeping resources and books.

Building beekeeping equipment yourself before you’re ready

Many hobbyists underestimate the precision needed to build boxes and frames that work with standard parts.

Foxhound reports lumber prices and hidden complexity often push DIY past supplier costs unless you plan 10+ hives. Minor dimension errors break compatibility with a standard hive and slow every inspection.

Where DIY goes wrong: boxes, frames, and “one less frame” issues

Small deviations in interior measurements allow burr comb and pinch points. That harms brood flow and forces extra handling.

The “one less frame” error invites cross‑comb and bee space problems. Leave every frame slot as designed; removing one to save time creates larger headaches during inspections.

When to buy equipment to protect your time and colony health

Buy core components first: box parts, frames, bottom boards, and covers from a reputable supplier save time and reduce risk. Supplier gear ensures correct spacing so bees build predictable comb and brood.

- Cutting frames is tedious and imprecise without jigs.

- Hidden costs include specialized blades and shop hours that steal time from colony care.

- DIY only after you’ve handled standard gear and can reproduce exact measurements reliably.

Value your time. Reliable equipment keeps inspections efficient and reduces stress on bees. Predictable hardware also makes it easier to get help or swap parts mid‑season.

For a quick refresher on beginner issues, see beginner mistakes.

Not understanding frames and bee space

A practiced glance at a single frame often reveals the colony’s biggest needs. Foxhound highlights that poor frame handling is a frequent source of problems.

Reading frames: brood, pollen, nectar, and capped honey

Define bee space. Bee space is the 1/4–3/8 inch gap bees use to move. Correct spacing prevents burr comb and cross‑comb that slow inspections.

How to read a frame: look for eggs at cell bases, larvae and capped brood, bands of stored pollen, nectar pools, and capped honey. Each element shows needs: eggs mean queen activity, pollen indicates protein for brood, and capped honey shows winter stores.

- Healthy brood: dense, contiguous brood with few scattered gaps — a sign of a strong queen.

- Pollen bands often flank the brood nest; nectar arcs above or around it. Balance supports steady growth.

- Return frames in order and keep consistent spacing to avoid crushing bees or rolling brood.

| Frame Feature | What it shows | Action |

|---|---|---|

| Eggs | Active egg laying | Monitor queen, no intervention if pattern solid |

| Capped brood | Developing workers | Ensure ventilation and space |

| Pollen | Protein supply | Supplement if scarce |

| Capped honey | Stored energy | Delay harvest until surplus |

Rotate old dark frames over seasons to reduce pathogen load. Frame reading guides feeding, supering, or queen steps more reliably than watching entrance traffic. Practice calm, deliberate handling; confident frame work underpins every beekeeping decision.

Missing queen problems and not checking for eggs

You can’t judge queen health from entrance activity alone; look inside for proof.

Mann Lake warns that queenlessness can be deceptive: a hive may show steady worker traffic while brood declines. Dadant advises confirming eggs at each inspection because eggs mean the queen laid within about three days.

Spotting queenlessness: eggs, brood pattern, and behavior

Check frames for recent eggs first. No eggs, scattered brood, or drone‑heavy cells often signal a failing or missing queen.

Behavioral clues include sudden agitation, a low roar, or many emergency queen cells built fast.

Next steps if the queen is gone or failing

Act decisively but gently. Options: give a frame with eggs from a healthy hive, introduce a mated queen in a cage, or allow a strong colony to raise one if timing is right.

Handle introductions carefully and re‑check in a week to confirm acceptance and resumed brood pattern. Record each intervention so you can track recovery.

| Sign | What to look for | Action |

|---|---|---|

| No eggs | Empty brood cells, no larvae | Introduce eggs frame or a mated queen |

| Scattered brood | Patches of capped brood, mixed ages missing | Monitor; consider requeening if pattern worsens |

| Emergency cells | Many queen cups or sealed queen cells | Decide: allow rearing or add a mated queen depending on season |

For a quick refresher on common early-season issues, see beginner mistakes. Timely checks for eggs and brood protect colony strength through key nectar flows.

Not feeding when nectar is scarce or during startup

When forage runs low or you start with a package, timely feeding keeps a colony alive through lean periods.

When to provide supplemental feed

Feed bees at these times: installing a package with few stores, during a poor nectar flow, or in fall when stores fall short of winter targets. Dadant advises planning for at least 50–60 lb of honey per hive; in cold regions aim toward ~100 lb.

Choose the right feed by season

Use 1:1 or 2:1 sugar syrup in spring build‑up so bees can take liquid and draw comb. In cold weather switch to dry sugar or fondant when bees cannot process liquid well.

Pollen and protein for brood rearing

Pollen patties support spring brood rearing when natural pollen is scarce. Offer patties sparingly, watch consumption, and remove if pests gather or mold appears.

Avoid overfeeding and robbing

Never feed purchased honey; it can carry disease. If you must feed syrup, avoid spilling and reduce entrances during dearth to deter robbing. Feed internally or between frames when possible.

- Feed packages consistently for about a month until they draw comb and store nectar and pollen.

- Heft hives or weigh bodies to judge stores rather than guessing.

- Limit syrup feeding during a heavy nectar flow to avoid diluting honey you plan to harvest.

Strategic feeding stabilizes the colony so it can grow into and out of spring and survive winter.

Harvesting too much honey in the first year

Taking honey too early can leave a colony short of the stores it needs for cold months.

Harvest decisions in year one should favor the bees. In most areas, colonies use their first season to build comb and stores. Removing much honey now often forces emergency feeding and raises winter risk.

How much to leave for winter in your area

Regional targets help set realistic goals. Dadant recommends leaving 50–60 lb of honey in most zones. In colder climates plan closer to 100 lb. Local mentors refine that number for your area and forage patterns.

Signs your colony has true surplus honey

True surplus is capped honey in supers beyond brood box needs. Check that frames are fully capped, nectar flows are steady, and there are no signs of dearth.

- Assess weight: heft the hive body to judge stores rather than trusting the entrance view.

- Verify frames: capped honey across multiple frames in the super indicates surplus.

- Confirm flow: avoid taking honey during erratic nectar times.

| Region | Leave for winter | Surplus sign |

|---|---|---|

| Temperate (most U.S. zones) | 50–60 lb | Fully capped supers over brood boxes |

| Cold climates (northern states) | ~100 lb | Capped honey across several boxes and strong late-season flow |

| Warm/rural areas | 50–75 lb (adjust by mentor) | Consistent nectar and drawn comb beyond brood nest |

Patience pays: prioritize colony strength over early yields; second-season harvests are usually larger and less risky.

After any removal, check that capped stores remain adjacent to the brood for easy winter access. Validate decisions with local beekeepers and plan harvest goals for year two when comb is mature and the hive is established.

Neglecting records: no notes on hive health and activity

Noting what you see at each visit creates a timeline that protects colony health. Dadant recommends written logs or apps so a beekeeper can compare queen performance and evaluate hive styles over a season.

What to track: simple items that matter

Keep brief entries after each inspection. Record queen status, presence of eggs, brood pattern, stores, mite counts, and temperament.

- Note weather, forage, and the exact time of day to interpret behavior and activity.

- Count or estimate bee traffic at the entrance and compare it to your baseline.

- Log dead bees found, recent treatments, and any feeding you provided.

- Use photos of frames to document comb building and brood area progress.

“Concise notes after each inspection save time and reduce unnecessary re‑opening.”

| Track Item | Why it matters | How often |

|---|---|---|

| Queen status / eggs | Confirms laying and colony continuity | Every inspection |

| Mite count | Protects health and treatment timing | Monthly or after interventions |

| Bee traffic entrance | Shows foraging strength and sudden declines | Quick count each visit |

| Stores & temperament | Guides feeding and handling approach | Every inspection |

Standardized checklists make each visit efficient and less disruptive. Compare colonies side by side to evaluate equipment choices and management tweaks. Over time, records trigger earlier, better‑targeted actions that protect your bees and save you time.

Poor hive placement and entrance management

Positioning affects flight lines, moisture control, and how safely you can handle boxes. Good placement saves time and reduces stress for both keeper and colony.

Sun, windbreaks, and stand stability

Full sun reduces damp, speeds morning flights, and helps internal temperatures. Dadant recommends full sun and a stable stand with ~10‑foot clear working radius.

Level boxes keep frames aligned and stop drifting comb. Check stands after storms and settle issues promptly.

Directing bee traffic at the entrance away from people and pets

Orient the entrance so flight lanes avoid walkways, pools, and play areas. That reduces conflict and concentrates bee traffic away from living spaces.

Adjust entrance size by season to balance ventilation and defense. Nearby water and strong forage change where bees queue and how fast they return.

- Keep a clear work area to lift boxes and stage tools safely.

- Use windbreaks to cut drafts but keep a good flight path.

- Recheck placement each season; small moves save time later.

| Factor | Recommended action | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Sun exposure | Full morning sun | Lower moisture, earlier flights |

| Stand stability | Level, secure stand | Frame alignment, safer inspections |

| Entrance orientation | Away from high traffic | Less conflict with people and pets |

Assuming bees can take care of themselves

Don’t accept the hands‑off myth. Foxhound lists assuming bees self-manage as a key error. Modern pests, variable forage, and weather mean colonies need seasonal attention and timely interventions.

Spring: confirm eggs and brood, feed if stores are low, add space as frames fill, and watch for swarm signs. Quick checks in this window set the pace for the year.

Summer: add supers for flow, manage ventilation and water, and note dearth transitions so you can act before stores drop.

Fall: assess stores, combine weak hives, reduce entrances, and confirm queen performance before cold weather arrives.

Winter: ensure sufficient honey, control moisture and ventilation, and avoid unnecessary disturbances that cost the colony energy.

- Time‑bound tasks matter: missing a window can set a hive back a season.

- Plan equipment and treatments ahead so you have what you need when it’s needed.

- Compare checklists between colonies to tailor actions to each colony’s condition.

“Small, consistent actions are the surest way to steward healthy colonies.”

Beekeeping that stays ahead of seasons reduces emergency fixes and stress for the bees. Over a year, steady care protects growth and improves survival.

Conclusion

A steady, fundamentals‑first approach is the clearest way to shepherd a hive through its first year.

Focus on basics: safety, efficient inspections, and sound equipment choices set the foundation. Learn to read frames, eggs, and brood so small issues do not become major mistakes.

Lean on local clubs and mentors to match actions to regional flows and winter needs. Keep concise records; notes turn observations into informed choices at the next visit.

Be disciplined with feeding and harvest so your bees enter winter strong. Pick a practiced way that fits your goals and local conditions, then follow it consistently.

With measured care and the cadence outlined here, beekeepers reduce risk and help their colonies thrive year after year.

FAQ

What should I expect during the first year of beekeeping?

Expect a steep learning curve. The first year is about establishing the colony, learning local nectar and pollen flows, and timing inspections. Plan regular checks in spring and summer, watch for brood pattern, queen activity, and seasonal needs like feeding or ventilation. Local climate and forage determine timing more than a calendar.

How much time do hive inspections and equipment prep take?

Inspections usually take 10–30 minutes per hive when you move efficiently; the first few visits may take longer. Equipment prep—assembling boxes, frames, and a smoker—can take several hours up front. Maintain a routine: prep gear the night before and minimize disturbance during checks.

Why is beekeeping so dependent on local conditions?

Bees respond to local forage, temperature, and weather patterns. In the United States, nectar flows and winter severity vary by region. Local clubs, state extension services, and experienced beekeepers in your area provide guidance tailored to those conditions.

What protective gear do I really need?

A well‑fitting veil or full suit, gloves if you prefer them, and closed footwear are essential. A veil from brands like Paradise or BeeSafe and a ventilated jacket work well. Good gear reduces stress for both you and the colony, and helps you focus on inspections instead of stings.

How do I use smoke correctly?

Light the smoker with dry fuel like burlap or pine needles, keep a steady cool smoke, and puff at the entrance then under the lid. Use just enough smoke to calm guard bees—heavy smoke can stress the colony. Practice at home so you can apply smoke smoothly during inspections.

How often should I open the hive in spring and summer?

In early spring, inspect every 7–10 days to monitor queen laying and build‑up. During peak season, inspections every 10–14 days suffice unless you detect problems. Avoid excessive openings; each inspection disturbs the colony and wastes time.

What is an efficient inspection routine?

Start at the entrance to observe traffic, then remove frames one at a time from the side, checking brood, eggs, and stores. Look for the queen or signs of her (eggs, consistent brood pattern), brood diseases, and enough space for expansion. Replace frames in original order to preserve orientation.

Which resources should I consult before getting bees?

Use reputable books like Dave Cushman’s guides, courses from your county extension, and resources from the American Beekeeping Federation or Bee Informed Partnership. Local beekeeping clubs and state apiarists provide practical, region‑specific advice.

How much should I rely on other beekeepers’ opinions?

Listen broadly but weigh advice against local conditions and scientific sources. Experienced mentors help, but don’t adopt every tip you hear. Test techniques on one hive before applying them across your apiary.

Should I join a local beekeeping club?

Yes. Clubs connect you to mentors, swarm alerts, equipment swaps, and local best practices. They also offer hands‑on workshops that accelerate learning and help you avoid region‑specific pitfalls.

Is DIY equipment a good idea for beginners?

Basic DIY work can save money, but precise dimensions matter. Poorly built boxes or incorrect bee space cause burr comb and frame issues. Consider buying critical items like frames and foundation from Mann Lake, Brushy Mountain, or local suppliers until you gain experience.

What is “one less frame” and why does it matter?

“One less frame” refers to leaving fewer frames than standard in a box, which can create unwanted gaps and burr comb. Proper frame spacing preserves bee space and prevents cross‑combing. Use standard equipment or carefully follow dimension plans if building boxes.

How do I read frames for brood, pollen, and honey?

Brood frames show capped brood and emerging workers; look for a solid, consistent pattern. Pollen appears as colored patches near brood. Nectar shows wet uncapped cells and capped honey has a smooth wax capping. Regular checks help you track colony health and stores.

How can I spot queen problems quickly?

Look for irregular brood patterns, many open cells with no eggs, laying workers, or sudden behavior changes. Presence of eggs and mixed brood stages indicates a laying queen. If you find no eggs after a full brood cycle, take corrective steps promptly.

What should I do if the queen is failing or gone?

Options include requeening with a mated queen from a reputable supplier, introducing a queen cell, or combining with another colony using a newspaper method. Choose based on your experience level and local availability of queens.

When should I feed bees sugar water or provide protein?

Feed sugar water at startup, during long nectar dearths, or when stores run low—use a 1:1 mix for spring build‑up and 2:1 for winter stores. Offer pollen patties or protein supplements in early spring to support brood rearing. Feed carefully to avoid robbing.

How do I avoid overfeeding and triggering robbing?

Use internal feeders or hive top feeders with small openings, feed during low foraging times, and remove or reduce feeding as natural forage returns. Keep entrances reduced and monitor nearby hives to prevent robber bees from attracting predators.

How much honey can I harvest in the first year?

Avoid heavy harvesting the first year. Leave enough honey for winter—amounts vary by region. A conservative approach is to leave all frames of capped honey unless you’re in a strong, well‑prepared colony with verified surplus.

How do I know if the colony has true surplus honey?

Surplus shows as multiple fully capped honey frames above brood and adequate stores remaining in lower boxes. If bees are still foraging actively and brood has space, you may have harvestable frames. When in doubt, err on the side of leaving stores.

What records should I keep and why?

Track hive inspections, queen status, mite counts, treatments, feedings, and weather. Note bee traffic at the entrance and brood observations. Consistent records reveal trends, help diagnose issues, and improve decision making over seasons.

Where should I place my hive for best results?

Choose a site with morning sun, afternoon shade, wind protection, and stable stands. Position the entrance away from high‑traffic areas and direct bee flight upwards and away from neighbors. Ensure easy access for inspections and water nearby.

What seasonal checks should I follow?

Use a checklist: spring build‑up (queen, brood, feeding), summer flow (swarm prevention, supering), fall prep (stores, mite treatments), and winter care (insulation, ventilation, moisture control). Regular seasonal tasks keep colonies resilient.

How do I control mites and other health threats?

Perform regular mite counts (alcohol wash, sugar shake, or sticky boards), rotate treatments like oxalic acid or formic formulations when thresholds are met, and use integrated pest management. Monitor for American foulbrood, nosema, and other diseases and consult local extension for lab testing.