This introduction frames modern shock qualification for products that must survive explosive or impact events during manufacture, shipping, or use.

Testing starts with a measured acceleration input in the time domain and ends with a shaker-ready pulse. Engineers compute a shock response spectrum from recorded data (SRA) and then use SRS synthesis to create a feasible test waveform.

Why this matters: the spectrum plots peak single-degree-of-freedom responses versus frequency, so many time histories can map to the same spectrum. SRS quantifies damage potential while synthesis respects shaker limits for acceleration, velocity, and displacement.

Industry tools such as Simcenter Testlab and Data Physics/Spider provide profile editors, fractional-octave spacing, damping options, and synthesis modes. Good practice includes DC removal or high-pass filtering and iterative tuning until constraints and error metrics meet test goals.

Key Takeaways

- SRA derives a shock response spectrum from time traces; SRS synthesis makes shaker-ready pulses.

- The spectrum captures peak system behavior, not full waveform history.

- Manage damping, frequency spacing, and acquisition fidelity to ensure valid results.

- Use Testlab or Data Physics/Spider tools for profile editing and synthesis.

- Apply DC removal and iterate until shaker constraints and target error are acceptable.

Understanding shock response fundamentals and scope for today’s testing

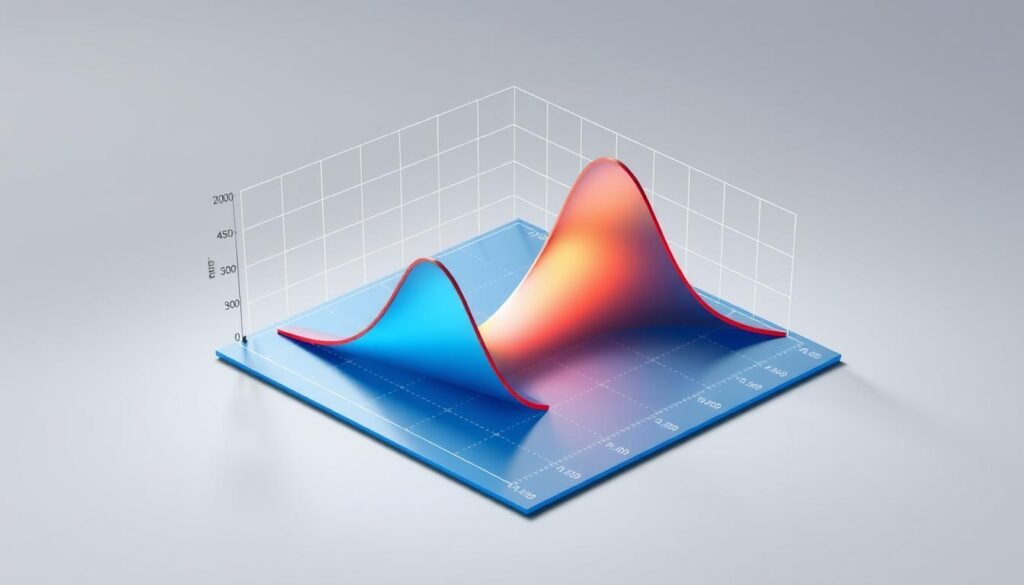

Practically, a shock response spectrum shows how a bank of single-degree-of-freedom systems peak when driven by the same transient input.

What a Shock Response Spectrum represents in practice

The SRS is built by applying a time-domain pulse to many SDOF filters with the same damping and different natural frequencies.

For each system, compute the time response and record the peak acceleration; plot that peak versus natural frequency on a logarithmic grid.

Primary vs. residual response and why it matters

Primary peaks occur during the forcing pulse and identify the parts of the input that most threaten components.

Residual peaks appear after the pulse ends and indicate how long a system rings, which can drive cumulative vibration damage.

- Damping and Q: Q = 1/(2ξ). Low damping raises resonance amplification and higher SRS peaks.

- Types: Maxi-max, primary positive/negative, and residual positive/negative are common reporting variants.

- Practical targets: ~5% damping for pyrotechnic events and ~2% for earthquake testing are typical choices.

Because transmissibility amplifies near a natural frequency, an SRS peak often exceeds the raw pulse peak acceleration. Use the SRS to set compact, frequency-aware targets for shaker synthesis without needing an identical time-domain clone.

Hive-shock response analysis: core concepts, terminology, and data flow

Convert measured acceleration into test-ready targets by computing a shock response spectrum from a transient time trace. SRA applies the input through many single-degree-of-freedom systems to capture peak behavior across frequency.

From time domain to SRS and back

SRA produces a response spectrum; SRS synthesis then finds a time waveform that matches that target spectrum while meeting shaker limits. Many waveforms can fit one spectrum, so synthesis is under-determined and must honor acceleration, velocity, and displacement bounds.

SDOF basics, binning, and SRS types

A single-degree-of-freedom model links stiffness and mass to natural frequency; damping controls resonance and Q = 1/(2ξ). Fractional-octave spacing (1/1 to 1/48) places filters logarithmically for proportional bandwidth analysis.

- Data flow: time-domain acceleration → SRA bank of SDOF → shock response spectrum → SRS synthesis → synthesized pulse.

- Types: Maxi-max (log-log), primary and residual signed spectra offer diagnostic value.

How to perform a complete analysis workflow from raw input to synthesized pulse

Begin the workflow by capturing a clean acceleration time trace with properly mounted accelerometers and verified sampling settings.

Acquire acceleration time history

Mount appropriate accelerometers and set sampling high enough to capture target frequencies. Check headroom to avoid clipping and save raw data for SRS computation.

Compute the shock response spectrum

Choose damping (for example, 2% or 5%) and frequency bounds that bracket structural modes. Use fractional-octave binning and export the computed spectrum for synthesis.

Synthesize and validate

Import the spectrum into a profile editor (Simcenter Shock Control or Navigator workbook) and synthesize a time waveform. Constrain acceleration, velocity, and displacement to match shaker limits.

Iterate until limits are green and spectral error is acceptable. Use DC removal or a high-pass filter so start/end velocity and displacement are near zero.

“Enable filtered integration in Simcenter by editing TestLabEnvironmental.ini to reduce discontinuities in integrated velocity and displacement.”

| Step | Tool | Key check |

|---|---|---|

| Acquire | SCADAS / Simcenter | Sampling, headroom, clipping |

| Compute SRS | Navigator workbook | Damping, frequency bounds |

| Synthesize | Shock Control Profile Editor | Accel/vel/disp limits green |

| Validate | Testlab settings | Filtered integration, DC removal |

- Envelope multiple measured environments (pavement, Belgian blocks, potholes) to capture worst-case damage.

Tools, parameters, and settings that drive reliable results

Choose tools and fix parameters early so synthesis converges quickly and tests stay practical.

Simcenter Testlab Shock Control: SRS profile editor and time synthesis

Set Reference Pulse to SRS, import the target spectrum into the Profile Editor, and confirm min/max frequency bounds. Use the Time Synthesis tab to generate an initial pulse from components (wavelet, damped sine, chirp).

Observe spectral error and limit status for acceleration, velocity, and displacement. Iterate component mix until limits are green and the spectral fit is acceptable.

Data Physics / Spider SRS options

Pick a reference frequency, set low/high cutoffs, and choose damping ratio or Q. Select SRS type (Maximax, Positive, Negative) and fractional octave spacing (1/1 to 1/48).

Choose windowing (Sine, Hann, Exponential, Rectangular) to control leakage. Spider records time streams and computes multiple spectra per channel for comparison.

Key parameters, waveform types, and quality checks

- Component choices: use wavelet or damped sine for narrow peaks; chirps for broadband; mix to speed convergence.

- Damping/Q: set ξ (e.g., 0.05 → Q=10) and document it in reports.

- Validation: overlay measured vs target spectrum, monitor peak acceleration, and check integrated velocity/displacement.

“Log configuration and review raw time streams before test runs.”

Applications, test planning, and interpretation of results

Plan tests by linking spectral peaks to likely damage at a product’s natural modes. The shock response spectrum reveals which frequencies drive the highest system amplification and therefore the greatest damage potential.

Linking peak response to damage potential at natural frequencies

Most severe damage occurs at or near a product’s natural frequency. Single-degree-of-freedom models predict how an input pulse maps to peak acceleration at those bands.

Use peaks to prioritize mitigation. When a peak aligns with a critical component mode, consider notching, stiffening, or damping to reduce vibrational risk.

Selecting SRS targets for earthquakes, drop impacts, and pyroshock

Damping guidance: use ~2% damping for seismic testing of flexible systems and ~5% for pyrotechnic events common in aerospace.

- Derive an SRS from recorded earthquakes, drops, or pyro events and envelope representative data to form robust targets.

- For drop-impact tests, compute a Maxi-max spectrum at suitable fractional-octave spacing, then synthesize a waveform that meets shaker stroke and acceleration limits.

- For pyroshock, use high frequency bounds and fine spacing (1/12 or finer) to capture short, high-frequency-rich content.

“SRS peaks can exceed the original pulse peak acceleration because resonance amplification raises spectral amplitudes in critical bands.”

Acceptance: compare measured test spectra against the target SRS, log deviations and margins, and document any notching justified by structural analysis or safety needs.

Conclusion

Turn measured transients into actionable test targets: compute a clean shock response spectrum from time-domain acceleration data, choose sensible damping and fractional-octave spacing, and synthesize an srs waveform that meets shaker limits.

Focus on peaks near a product’s natural frequency since those values drive most damage. Always record damping or Q alongside the spectrum to keep tests traceable and comparable.

Execute with discipline: validate acceleration, velocity, and displacement against limits. Use DC removal or a high-pass filter and enable filtered integration to reduce end-condition errors.

Envelope multiple environments, apply appropriate damping (for example, 2% for seismic, 5% for pyro), and use Simcenter Testlab or Data Physics/Spider for iterative convergence. Document all parameters and maintain configuration control so future tests and correlation remain credible.

FAQ

What does a shock response spectrum represent in practice?

A shock response spectrum (SRS) plots the peak acceleration that single-degree-of-freedom (SDOF) oscillators would experience across a range of natural frequencies and a given damping. It helps engineers see which frequencies are most excited by a transient event, indicating potential damage to structures or components that have matching natural frequencies.

How do primary and residual responses differ and why does it matter?

Primary response shows the immediate peak caused by the input pulse, while residual response captures longer-term or lower-frequency motion remaining after the main shock. Distinguishing them matters because the primary peak often controls high-frequency damage, while residual motion can affect low-frequency systems and cumulative stress. Both guide mitigation and design choices.

When should I use SRA, SRS, or synthesis in my workflow?

Use time-domain shock response (SRA) when you need direct insight from the measured waveform. Use SRS for frequency-focused design and qualification, especially when comparing to component natural frequencies. Apply time synthesis to generate a reproducible test pulse that matches a target SRS for shaker verification or qualification testing.

What is single-degree-of-freedom modeling and which parameters matter most?

SDOF modeling treats each mode as a mass-spring-damper system characterized by natural frequency, damping ratio (or quality factor Q), and response to input acceleration. The natural frequency and damping govern peak response amplitude and bandwidth, so accurate selection of these values is critical for meaningful spectra.

How do fractional octave spacing and binning affect spectra?

Fractional octave spacing defines frequency sample intervals and affects spectral resolution. Wider bins smooth peaks and risk missing narrow resonances; tighter bins increase resolution but add noise sensitivity. Choose spacing based on the frequency content and the precision needed for identifying natural frequencies.

What SRS types should I know (Maxi-max, primary, residual)?

Maxi-max SRS captures the absolute maximum envelope across all time; primary positive/negative isolate the first dominant peak polarity; residual positive/negative show long-duration baseline shifts. Each type serves a purpose: maxi-max for worst-case design, primary for immediate shock effects, residual for low-frequency concerns.

What are the key steps to acquire a valid acceleration time history?

Use properly mounted accelerometers with adequate bandwidth and sensitivity, set a sampling rate at least 10x the highest interest frequency, verify anti-aliasing filters, and perform pre-test checks for clipping or saturation. Validate signal integrity by inspecting baseline, noise floor, and timing synchronization.

How do I compute an SRS—what damping and frequency limits should I pick?

Select a damping ratio reflecting the real system or standard (commonly 5% for many electronics). Set frequency bounds to cover below the lowest mode of interest to above the highest expected excitation. Ensure fine enough frequency resolution near critical natural frequencies to capture peak responses.

How is a time waveform synthesized to match a target SRS within shaker limits?

Synthesis algorithms iteratively shape a time signal so its computed SRS approaches the target while respecting shaker limits for acceleration, velocity, and displacement. The process balances spectral content, pulse duration, and phase to produce a physically realizable waveform for the available shaker system.

What iteration and validation checks should follow synthesis?

After synthesis, verify that measured SRS matches the target within tolerances, and confirm shaker acceleration, velocity, and displacement limits were not exceeded. Check waveform quality: no clipping, acceptable harmonic content, and acceptable residuals. Repeat synthesis if discrepancies remain.

How can I mitigate discontinuities and DC offsets in shock signals?

Apply DC removal and baseline correction, use high-pass filtering with appropriate corner frequency to avoid altering low-frequency content, and window the pulse to reduce edge effects. Ensure filters do not distort the spectral content relevant to device natural frequencies.

How do I combine multiple environments to represent worst-case damage?

Envelope multiple SRS datasets by taking the maximum at each frequency to form a composite spectrum that represents worst-case excitation. Consider weighting by occurrence probability or mission phases when appropriate, and validate that the enveloped spectrum remains physically realistic for synthesis.

What tools offer reliable SRS editing and time synthesis capabilities?

Commercial packages like Siemens Simcenter Testlab and Data Physics’ Spider provide SRS profile editors, synthesis modules, and analysis options. Choose tools that support the required damping models, spectral types, and shaker constraint inputs for accurate closed-loop testing.

Which analysis parameters most influence SRS outcomes?

Damping ratio (or Q), frequency bounds, fractional-octave spacing, and sample rate dominate SRS results. Windowing, filtering, and whether you compute positive/negative or absolute envelopes also shape the final spectrum and its interpretation for design or testing.

What waveform types and quality checks should I use for testing?

Use burst pulses, synthesized random-frequency content, or measured-replay depending on objectives. Check for phase coherence, absence of clipping, acceptable harmonic distortion, and matching SRS within specified tolerances. Verify the waveform does not violate shaker acceleration, velocity, or displacement limits.

How does peak response at a natural frequency relate to damage potential?

Peak acceleration at a system’s natural frequency indicates the highest dynamic amplification; if the SRS shows large peaks at those frequencies, the component risks fatigue or immediate failure. Use modal data to map SRS peaks to structural modes and prioritize mitigation or design changes accordingly.

How do I choose SRS targets for earthquakes, drops, and pyroshock tests?

For earthquakes, emphasize low-frequency content and residual motion; for drops, include broad-band transient pulses with midband energy; for pyroshock, focus on very high-frequency peaks with short duration. Base target selection on field measurements, standards like MIL-STD or DO-160, and the equipment’s modal characteristics.