Swarming is the natural process by which a honey bee colony splits to form a new home. Workers build special cells, the queen reduces weight to fly, and about half the workers leave to cluster nearby while scouts search for a cavity.

In the United States this process peaks during the spring nectar flow, often March through May. A primary swarm is most common then; later, smaller casts may follow. Swarms are usually less defensive than a full hive because they lack brood and stores, but people should keep distance and stay calm.

This guide takes a practical, step-by-step approach for beekeeping decisions. You will learn how to spot early signs, tell queen cell types apart, and use timed inspections, space management, queen quality, and controlled splits to prevent or mimic natural division. Humane responses include contacting local beekeepers for safe removal rather than spraying.

Key Takeaways

- Swarming is a colony’s natural reproduction method.

- Peak season is spring during nectar flow in the U.S.

- Prevent with space management, inspections, and timely splits.

- Swarms tend to be less defensive but should be treated cautiously.

- Controlled splits preserve honey production and colony strength.

- Contact local beekeepers for safe, humane removals.

What a honey bee swarm is and why colonies split

When a hive becomes too crowded, the colony often prepares to split into two working groups. This reproductive split begins when internal congestion and weak distribution of the queen’s pheromones prompt workers to build special cells.

The typical process follows a clear order: workers construct reproductive cups, the queen lays eggs into those prepared cells, foraging slows, and the queen reduces weight to fly. At departure, about half the population—the exact number varies—leaves with the old queen.

The departing cluster rests nearby for hours or days while scout workers evaluate sites. Scouts guide the group to a new cavity, and the original colony retains enough bees to care for brood and stores while raising a successor queen.

- Purpose: a natural way for strong colonies to reproduce.

- Order: construction → egg laying → reduced activity → organized exit.

- Outcome: two functioning colonies from one, with first-emerging queens often eliminating rivals.

Bee swarming behavior in the United States: seasonal timing and nectar flow

Widespread spring forage creates the strongest seasonal push for colonies to divide across the U.S. Swarming activity usually coincides with the spring nectar flow when many plants bloom and resources are abundant. In most regions primary swarm season runs from March through May, though local climate and forage cycles shift exact timing.

Primary season and local variation

High nectar availability accelerates population growth and congestion inside the hive, which raises the colony’s reproductive impulse. Overwintered colonies that build strong early populations are prime candidates to issue a primary swarm as temperatures rise.

Later-season casts and practical advice

After-swarms later in the year are usually smaller and less likely to survive winter because they lack time to draw comb and store honey. Primary swarms commonly include the original queen; later casts often carry virgin queens and fewer workers.

- Action: add space ahead of major flows to reduce congestion.

- Tip: use local bloom calendars and extension reports to match inspections to your location’s forage curve.

- Result: timing awareness helps plan splits and prevent unexpected losses.

Early signs your hive is preparing to swarm

Early signals of an impending split often appear as changes in how the colony fills and uses its space. Watch regularly during the spring flow; small changes add up fast.

Crowding, bearding, and the “honey bound” brood nest

Look for wall-to-wall bees on frames and persistent bearding at the entrance, even on mild days. These are clear congestion indicators.

Honey bound conditions occur when nectar and honey push into brood frames, leaving less room for brood rearing. That squeeze raises the chance of a split.

Entrance traffic, drone population, and resource patterns

Heavy traffic across the full width of the entrance shows a peak population and limited interior space.

- All frames drawn and packed with brood, pollen, and nectar signal an active, resource-rich colony.

- Rising numbers of drone cells or adult drones point to ample resources and preparation for mating.

- Log frame-by-frame notes to track stores, brood pattern, and available space.

Orientation flights versus true swarm preparation

Orientation flights form orderly loops and figure-eights near the entrance. By contrast, an issuing swarm bursts into a chaotic, cloud-like mass.

“Early intervention before eggs appear in multiple queen cups gives beekeepers the best chance to prevent loss and preserve productivity.”

Act when you see these patterns: add drawn comb, shift boxes, or plan a split. For practical inspection tips see recognizing and avoiding swarms.

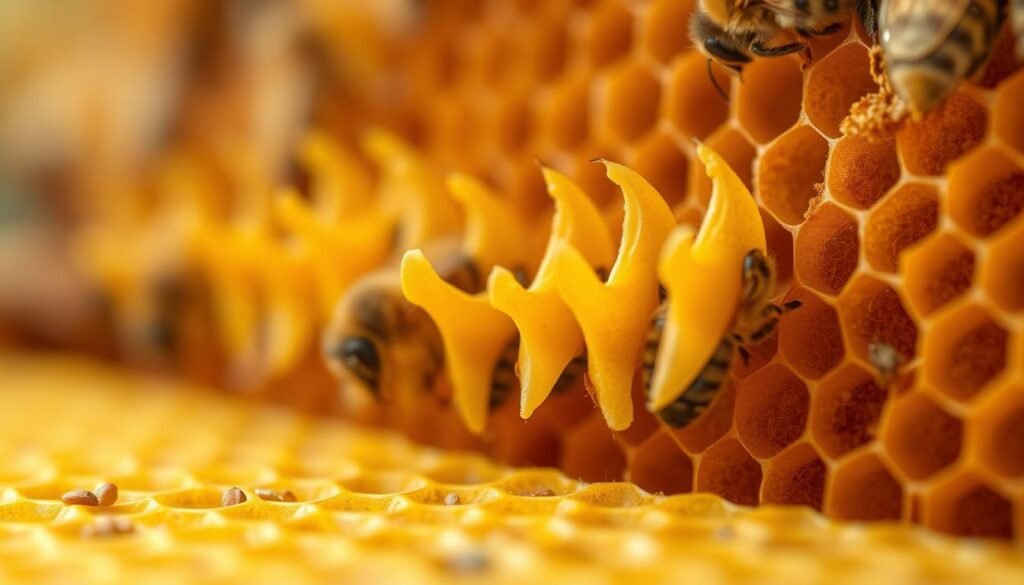

How to identify queen cups, swarm cells, and supersedure cells

Spotting the difference between casual cups and true queen-raising cells is a key skill for timely hive decisions.

Queen cups start as small, shallow cups on comb. If a cup contains an egg or tiny larva, it is active and suggests the colony is rearing a queen.

True queen cells — often called swarm cells — are large, peanut-shaped, and hang downward. They are commonly found along the bottom of brood frames, though placement can vary.

Supersedure cells tend to sit mid-frame and are few in number. They usually signal the colony plans to replace a failing queen rather than split.

Practical checks and timing

Check for eggs, larvae, or capped pupae inside any cell. Capped, peanut-shaped cells mean pupation is underway and a queen will emerge in about 16 days from the egg.

- Differentiate dummy cups from active cups by presence of eggs or larvae.

- Count and map cells: numerous same-age cells suggest an intent to leave; a few mid-frame cells suggest replacement.

- Look for ragged openings on the tip of a cell — that often marks a recent emergence.

Inspect all brood frames so isolated cells are not missed. Record whether cells contain eggs, brood, or are capped to guide whether to split, requeen, or monitor.

What triggers swarms: population pressure, limited space, and queen pheromones

Rapid colony growth can turn a calm hive into a pressure cooker of reproductive urgency. As worker numbers rise, available brood nest space can be consumed faster than new comb is drawn.

Reduced coverage of the queen pheromone across a crowded cluster signals workers to begin reproductive preparations. They build large queen cells and change feeding patterns to slim the current queen so she can fly.

Abundant nectar and pollen during a strong spring flow accelerate comb filling. When stores push into brood frames, the squeeze raises the chance that the colony will choose to divide.

- Rapid population growth outpaces brood space and intensifies the split impulse.

- Low pheromone distribution in dense clusters prompts workers to raise new queens.

- Older queens and certain genetics correlate with higher swarming risk.

The exact departure signal remains unclear, but congestion and pheromonal gradients are central. Practical interventions—adding boxes, balancing frames, and timely requeening—target these drivers directly.

Plan inspections around expected resource surges and act early. Forecasting the major nectar flows helps prevent a cascade from crowding to runaway queen cell proliferation.

Are swarms dangerous? Safety, behavior, and when to keep your distance

A clustered group on a tree limb is usually focused on protecting its queen and finding a new nesting site, not on attacking people. Most swarms are less defensive because they carry no brood or stored honey to guard.

Still, they will defend the cluster if prodded or sprayed. Keep a safe distance, avoid loud vibrations, and do not attempt to hose or smoke the group. Calm, slow movements reduce risk.

Duration varies. Many colonies move on within hours; weather or scouting delays can extend the stay to days. Keep children and pets away from the area until professionals arrive.

If a cluster settles near a house, contact local beekeepers and removal networks for humane collection and rehoming.

Do not spray. Spraying agitates the insects, worsens safety, and harms pollinators. If the group enters a structure, it is no longer transient and needs specialized removal—give exact site details when you call for help.

Prevention strategies before swarm season

Preventive work in late winter and early spring helps keep colonies calm during the big nectar push. A short checklist done before bloom saves time and protects hive productivity.

Manage space: add boxes, drawn comb, and relieve congestion

Add supers and provide drawn comb ahead of peak bloom to keep brood areas open. Do this before you see obvious bearding so the colony has room to expand.

Balance brood and resources to avoid a honey bound brood nest

Move and balance frames regularly so nectar and honey do not choke the brood. Equalizing frames between hives evens out pressure across the apiary and reduces emergency queen cell production.

Queen management: age, genetics, and requeening cadence

Track queen age and temperament. Many beekeepers requeen every few seasons to lower the natural urge to split and to improve genetics in the yard.

Timing your inspections around spring nectar flow

Increase inspection frequency just before and during the main nectar flow. Use population and resource assessments to decide when to add boxes rather than waiting for visible signs.

- Pre-season checklist: equipment ready, drawn comb inventory, and inspection calendar.

- Proactive spacing beats reactive fixes once multiple queen cells appear.

- Result: consistent prevention preserves honey production and cuts emergency interventions.

How to split hives to reduce swarming

Splitting a strong hive early in the season is a practical way to reduce the urge to swarm and grow your apiary.

When to act: Do splits in early spring before the main nectar flow and after nights stay warm enough for smaller groups. Favorable signs include a strong overwintered population, early pollen, visible queen cells, a queen older than one year, and early drone rearing.

When a colony is strong enough to split

Readiness looks like frames covered with bees and multiple frames of brood spread across boxes. Confirm consistent stores so each unit can feed larvae and the new queen.

Pros and cons of walk-away and swarm-control splits

Walk-away split is simpler. You can place frames and introduce a purchased queen to one unit and leave the other intact.

Swarm-control split requires finding the queen and moving her to a nuc while keeping brood and resources balanced. This method mimics natural order but needs more skill.

| Method | Skill needed | Primary benefit | Common drawback |

|---|---|---|---|

| Walk-away split | Low | Fast, uses purchased queen | Cost of queen; acceptance risk |

| Swarm-control split | Medium–High | Uses existing queen; natural mating | Requires finding queen; temporary loss of production |

| Both | Planning required | Brood break helps Varroa control | Short-term reduction in honey yield |

- Benefits: natural increase, brood break for mite management, possible nuc sales, and controlled population numbers.

- Drawbacks: temporary dip in honey, risk of failed queen acceptance, and added inspections.

Prepare in order: stage equipment, confirm adult numbers and stores, pick the method that matches your comfort with finding queens, and schedule follow-up checks to verify each unit is queenright. Document results to refine timing in future seasons.

Step-by-step: walk-away split with a purchased new queen

Using a purchased new queen in a walk-away split gives a predictable path to create a separate home while relieving congestion in the original hive. The method relies on nurse bee migration overnight and a careful, staged introduction.

Equipment checklist and setup

- Full set: hive body, bottom board, top cover, lid, entrance reducer, stand.

- Empty frames with drawn comb and a queen excluder.

- New queen (caged), basic tools, and record log for dates and notes.

Frame selection, queen excluder placement, and introducing the queen

- Remove two frames of brood (all stages) plus two frames of honey/pollen into a prepared box; gently shake bees off frames to direct nurse workers.

- Replace removed frames in the original hive with drawn comb; place the queen excluder on the original box and set the new box above it for about 24 hours so nurses move up to tend brood.

- After one day, move the upper box to its own bottom board and install the caged new queen in the center of the frames.

- Use the staged cork removal technique, then replace the cork with a small marshmallow to allow a gradual release and acceptance.

Follow-up checks: acceptance, eggs, and early brood

Return in about 2–3 days to confirm the queen has been released. Check again at 7–10 days for eggs; freshly laid eggs are the earliest reliable sign the introduced queen is functioning.

Best practices: keep entrances reduced initially, monitor traffic, align the split with local nectar flow for good nutrition, and record each step and date in order to repeat success.

Step-by-step: swarm-control split using a nuc

Placing the queen into a prepared nuc helps rebuild a balanced colony while the original hive raises a replacement. The goal is a compact, well-fed unit that becomes a reliable new home.

Finding the queen and configuring brood, food, and space

Locate the queen by scanning for an elongated abdomen and the cluster of attendants that follow her movement. Gently transfer her on a frame of brood into the nuc.

Arrange five frames: two outer frames of honey and pollen for food, two inner brood frames beside them, and one empty drawn comb in the center for immediate egg laying. Shake additional nurse bees from two brood frames into the nuc to ensure care.

Off-site placement, feeding 1:1 syrup, and growth checks

Move the nuc off-site for about seven days to reduce forager drift back to the original hive. Feed a steady supply of 1:1 sugar syrup to speed comb building and support early stores.

Check the nuc every 7–14 days during the first month. Confirm queen laying, brood development, and increasing population. Once stable, transfer the unit into full-size hives and return it to the apiary as its new home.

What to do when a swarm has already issued from the original hive

If your hive has already lost a large portion of its workers, check queen cells and frame counts right away. A rough, ragged opening at the bottom of a queen cell indicates a queen has emerged and likely left with a swarm.

Reading exit holes and population clues

Inspect cell placement and tally adults. Many bottom-hanging, capped cells plus a sudden population drop point to a swarm. A few mid-frame cells with a minor population change more likely mean supersedure.

Locating and capturing a nearby cluster

Scan the immediate location—trees, shrubs, and structures—since clusters often settle for hours or days. If you find a group, use a nuc or box with frames and a small entrance.

- Gently shake or brush clustered bees into the box, ensuring the queen is included.

- Leave the box near the cluster for a short time so stragglers join by scent.

- Close and move the unit to its permanent home; keep the entrance small initially.

Monitor the issuing hive for remaining capped cells and watch for eggs over the next days. If no eggs appear on a reasonable timeline, consider introducing a purchased queen. Record emergence and capture dates and plan follow-up inspections to confirm both units are queenright.

For additional resources on equipment and best practices, see this practical guide.

Humane removal, legal considerations, and when to call a beekeeper

When a cluster appears on private property, choose humane, practical options that protect people and pollinators. Quick contact with local networks reduces risk and preserves useful colonies.

Why not to spray and how to find help

Do not use insecticides. Spraying agitates bees, raises safety risks, and destroys pollinators that benefit gardens and crops. Instead, contact local beekeepers or a beekeeper association listed by your county extension.

- Search neighborhood groups, state beekeeping associations, or online swarm lists for rapid pickup.

- Provide exact location, accessible hours, and photos to speed response.

- Remember: destroying a cluster is usually legal but costly in safety and ecological value.

When bees move into buildings

When insects colonize a wall or chimney they are no longer a transient cluster and need full removal. Removing live bees plus comb prevents rot, pests, and recurring infestations that can persist into winter.

- Do not seal entrances before removal; that traps bees and increases damage.

- Coordinate live removal with experienced beekeepers and hire licensed contractors for repairs once the hive and comb are extracted.

- Document access points and photos of the site to plan scope and reduce wall damage.

| Issue | Recommended action | Who to call |

|---|---|---|

| Transient cluster on property | Call local beekeepers for live collection | Beekeeper networks / swarm lists |

| Colonies inside walls or chimney | Extract bees and comb; then repair structure | Beekeeper for removal; licensed contractor for repairs |

| Winter residual comb odor | Full cleanup to prevent pests and mold | Removal specialist and remediation contractor |

Timely, coordinated action limits structural harm and helps connect useful honey bee groups to managed homes. This approach protects neighbors, property, and pollinator populations.

Conclusion

Treating hive division as a predictable seasonal event helps beekeepers stay ahead.

Swarming is a natural reproductive response that peaks with spring nectar flows. Watch for crowding, honey-bound brood, rising drone numbers, and queen cells as early cues.

Act by adding space, balancing brood frames, and planning thoughtful queen replacement. Planned splits reduce pressure and keep a colony healthy into winter.

Align inspections with local bloom timing, keep clear records of dates and actions, and prepare equipment and contacts before the busy season begins.

If a cluster appears near homes, seek humane collection through local beekeeper networks to protect people and pollinators. These steps protect the hive and the surrounding community and encourage ongoing learning and collaboration.

FAQ

What causes a honey bee colony to split and form a swarm?

Colonies split when the population grows, space becomes limited, or the queen’s pheromones weaken. Workers build large queen cells and rear new queens. When conditions favor relocation—ample nectar flow, warm weather, and congestion—part of the colony will leave with the old queen to find a new home.

When is the primary swarm season in the United States and how does nectar flow affect it?

Primary season typically runs from early spring through late spring in most regions. Heavy nectar flow fuels rapid brood and population growth, creating the food resources and energy that drive colonies to reproduce. Local climate and bloom timing shift exact weeks, so monitor local forage patterns.

What early signs indicate a hive is preparing to split?

Look for crowding, persistent bearding at the entrance, and a honey-bound brood area with little space for new comb. Increased entrance traffic, higher drone numbers, and changes in resource storage also signal preparation. Orientation flights are normal, but coordinated queen cell construction is a clear warning.

How can I tell the difference between queen cups, swarm cells, and supersedure cells?

Queen cups are small, empty cups on comb margins. Swarm cells form on comb edges or face and are numerous and large during preparation to leave. Supersedure cells often appear singly and low, indicating replacement of a failing queen. Check location, number, and whether eggs or larvae are present to interpret intent.

What specific triggers push a colony to issue a swarm?

Triggers include high population density, constrained comb space, poor ventilation, a declining queen pheromone signal, and strong incoming nectar. Any combination that creates reproductive pressure can lead workers to rear new queens and split the colony.

Are temporary clusters or full swarms dangerous to people?

Most clusters are calm and not aggressive while they scout for a new home, but any large group can sting if provoked. Keep distance, avoid sudden movements, and contact a local beekeeper for safe removal. Trained responders can relocate colonies without lethal control.

What steps prevent splitting before the spring nectar flow peaks?

Preventive measures include adding boxes or frames of drawn comb to increase space, redistributing brood and honey to relieve a honey-bound nest, and timely requeening if the queen is old. Schedule inspections to catch queen cells early and manage genetic stock and timing to reduce pressure.

When is a colony strong enough to be split successfully?

A good candidate has excess brood, several frames of stores, and a healthy worker population. Look for ample nurse bees to support both units. Splitting during or just after a nectar flow gives the new unit resources to build up quickly.

What are the pros and cons of walk-away splits versus swarm-control splits?

Walk-away splits are simple and require a purchased queen; they reduce swarming risk but depend on successful queen acceptance. Swarm-control splits mimic natural division, keep both genetics, and can be done with a nuc, but they demand more skill to locate the queen and balance brood and food.

What equipment and steps are needed for a walk-away split with a purchased queen?

Prepare a new hive body, frames with drawn comb or foundation, feeders, and the purchased queen in her cage. Move frames of brood and stores into the new unit, introduce the caged queen on the center frame, and monitor acceptance, egg laying, and early brood development over the following weeks.

How do you perform a swarm-control split using a nuc?

Find and remove the laying queen, transfer several brood frames, food, and attendants into the nuc, and place the nuc off-site if possible. Feed 1:1 syrup to stimulate comb building. Check growth after 7–14 days and ensure the new queen or raised queen is laying.

What should I do if my colony has already issued a swarm?

Inspect the original hive for open exit holes on queen cells to confirm an issued swarm. Search the area for a clustered group, and contact local beekeepers to catch and install them into a prepared hive. If the original colony left, ensure remaining bees have a laying queen or manage requeening.

When is it appropriate to call a professional for removal, and why avoid spraying swarms?

Call a local beekeeper or pest removal service when swarms cluster on structures or in hard-to-reach locations. Spraying can kill beneficial insects and spread comb and brood, creating hazards. Professionals remove and rehome colonies humanely and advise on building repairs to prevent reoccupation.

How do legal considerations affect humane removal of colonies from buildings?

Local regulations vary; some jurisdictions require licensed removers for hives in structures. Always check municipal codes and work with certified responders who follow humane relocation and structural repair protocols. Documentation helps ensure compliance and reduces liability.