This practical guide surveys the common threats to honey production and colony health in the United States. It frames early detection as the top defense and links field signs to timely action.

You’ll learn to read brood and adult indicators, spot pests like Varroa and small hive beetle, and recognize bacterial, viral, and fungal agents. The guide pulls from Penn State Extension (MAAREC) briefings and Oklahoma State fact sheets that recommend routine, biweekly checks in spring and fall.

Integrated control strategies are emphasized so decisions stay data-driven and compliant with U.S. rules. The text highlights how combined stressors speed problem spread and why sanitation and surveillance often prevent severe losses.

Expect clear diagnostics, seasonal checklists, and action windows that help preserve honey yields and long-term beekeeping success. For further resources and reference material, see a curated list at beekeeping resources and books.

Key Takeaways

- Early, routine hive checks are critical to catch problems before they spread.

- Learn normal vs. abnormal brood and adult signs to avoid misdiagnosis.

- Parasites, viruses, and microbes interact to accelerate colony decline.

- Sanitation and targeted, integrated control reduce need for drastic measures.

- The guide offers seasonal checklists and practical field diagnostics.

Understanding Healthy Honey Bee Colonies to Spot Problems Early

Knowing what healthy larvae and capped brood look like is the first step in early hive diagnosis. A reliable baseline helps you spot subtle changes before they become serious.

Normal brood patterns and healthy larvae appearance

Hallmark signs: brood in compact, uniform patches; medium-brown, convex cappings; and pearly white, glistening larvae curled in a C at the base of each cell. These features indicate good nutrition and hive hygiene.

“Healthy brood fills the cell as it grows; capped worker brood is solid and not punctured.”

Queen, worker, and drone roles that influence resilience

The queen’s steady egg laying and pheromones keep colony behavior stable. Erratic laying or spotty patterning is an early warning of trouble.

Workers perform nursing, ventilation, and foraging. Drones support genetics and mating success. Gaps in these roles often reveal stress from poor food, crowding, or emerging disease.

- Inspect frames one by one to confirm brood staging and the queen’s presence.

- Watch adult bees for calm nurse work and steady foraging—signs of strong immunity.

- Note any sunken caps, punctures, or off-color larvae; these differ from normal convex cappings.

| Feature | Healthy Sign | What to Watch For | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Larvae | Pearly white, C-shaped | Off-color, sunken | Check nutrition; isolate frame |

| Worker brood | Medium-brown, convex caps | Punctured or missing caps | Inspect adjacent frames; monitor queen |

| Adult behavior | Calm, active nurses and foragers | Clustering, lethargy | Assess stores and ventilation |

| Colony layout | Even brood density; stores nearby | Crowding, brood gaps | Provide space or requeen if needed |

Regular, frame-by-frame inspections and attention to nutrition and space keep brood strong and make it easier to find problems early.

Bee diseases

Infections cross frames and hives when contaminated food, drifting workers, and shared gear create corridors for microbes and viruses.

Within a colony, trophallaxis and nurse-to-larva contact circulate bacterial and viral loads fast across brood frames. Contaminated brood food spreads European foulbrood and other bacterial agents.

Between hives, robbing and drifting amplify transmission, especially when subclinical infections go unnoticed. Shared tools, frames, and feeding gear move spores and viruses from one hive to another.

Key transmission notes

- Some AFB spores persist for years in honey, comb, and on equipment, so sanitation is essential.

- Varroa mites vector viruses; mite reproduction inside capped brood boosts infected numbers late in the season.

- Dense apiaries raise cross-colony risk during high foraging; limit unnecessary interchange to reduce pressure.

“Spore longevity and vector activity mean vigilant hygiene and scheduled monitoring are the best defense.”

Field Diagnostics and Early Warning Signs

A few simple field tests and sharp observation often separate minor stress from true infection in a hive. Quick checks save time and let you choose targeted treatment before colonies decline.

Brood and adult symptoms to watch for at the hive

Watch brood for sunken or punctured cappings, spotty patterns, discolored larvae, and uncapped pupae. These are red flags for bacterial or viral trouble inside cells.

Inspect adults for trembling, hairlessness, greasy sheen, crowding at entrances, and deformed wings in late summer. Such adult signs often point to paralysis viruses or DWV.

Simple tests: matchstick test, visual cues, and sampling schedules

Matchstick test: gently probe a suspect capped cell. If a sticky, brown, ropey thread pulls out, AFB is likely and you should escalate testing.

- Take standardized photos of frames to track subtle changes across hives.

- Do biweekly checks in spring and fall and add mite counts when symptoms appear.

- Keep a clean set of equipment and alcohol wipes to sanitize tools between inspections.

“Early detection often allows less disruptive interventions that preserve colony strength.”

| Sign | What to look for | Immediate action |

|---|---|---|

| Brood | Sunken caps, discolored larvae, spotty cells | Photo record, sample, consider lab kit |

| Adults | Trembling, hairless, deformed wings | Isolate hive if severe, check mites |

| AFB test | Brown, ropey remains on probe | Send sample to lab; follow USDA/local protocol |

Viral Diseases: Identification, Transmission, and Control

Several common viruses produce recognizable signs in adults and larvae that guide rapid response. Early visual checks and timely mite control reduce amplification and protect winter survival.

Deformed wing virus and Varroa-associated wing deformities

Deformed wing virus (DWV) shows as stubby, malformed wings and poor flight in adults. Pupae may die in uncapped cells. Varroa destructor drives seasonal spread by amplifying the virus within colonies.

Acute and chronic paralysis presentations

Acute and chronic paralysis viruses produce hairless, trembling adults with odd wing positions. High brood losses in capped cells and dead bees near hive entrances are common when pressure is high.

Israeli acute paralysis virus (IAPV)

IAPV can be covert before rapid colony decline. It affects multiple life stages; Varroa-mediated transmission often turns low-level infection into a crisis.

Sacbrood virus in spring brood

Sacbrood virus creates fluid-filled sacs around dead larvae and later fragile, gondola-shaped scales. Protein stress in spring raises incidence; remove affected brood and improve nutrition.

“Rigorous Varroa management, sanitation, and targeted protein support are the most effective controls.”

- Distinguish DWV by deformed wings and impaired flight.

- Watch for hairless, trembling adults to flag paralysis viruses.

- Time mite treatments before fall to protect colonies from virus amplification.

- Use removal of infected brood and protein supplements for sacbrood recovery.

For background on virus biology and monitoring, see viruses in honey bees.

Bacterial Brood Diseases: Foulbroods and Their Management

Bacterial brood infections demand quick recognition and strict sanitation to protect honey yields and colony vigor.

American foulbrood — signs, spores, and options

American foulbrood (Paenibacillus larvae) is marked by sunken or punctured caps and a foul smell. Use the matchstick test: ropey, brown larval remains strongly indicate AFB.

Paenibacillus larvae spores survive on comb and in honey for years, so reusing equipment without proper scorching risks reinfection. In some states AFB is reportable and treatments follow strict rules; antibiotic use may require veterinary oversight under a VFD.

European foulbrood — stress links and control

European foulbrood produces rapid death in non-capped brood. Larvae discolor from white to yellow to brown and brood patterns become spotty with a sour odor.

Manage EFB by improving nutrition, adding protein patties, and requeening when needed. Terramycin (oxytetracycline) is an FDA-approved option where regulations allow. Minimize frame transfers and control robbing to slow spread.

“Decisive, early intervention protects colony strength and honey production potential.”

| Feature | American foulbrood | European foulbrood | Key action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical cells | Sunken, punctured caps | Non-capped, spotty brood | Isolate and sample; photo record |

| Larval sign | Ropy, brown remains on probe | White → yellow → brown; rapid death | Improve nutrition; consider lab test |

| Persistence | Spores survive years in honey/equipment | Related to stress and poor protein | Scorch or burn contaminated wood; sanitize tools |

| Treatment | Reportable; VFD/antibiotic limits; burning if severe | Protein support, requeening, targeted antibiotic if needed | Follow state rules and vet guidance; limit frame movement |

For reporting and management guidance on american foulbrood see american foulbrood guidance. For practical apiary practices when expanding or managing equipment, consult apiary expansion tips.

Fungal and Microsporidian Infections Affecting Bees

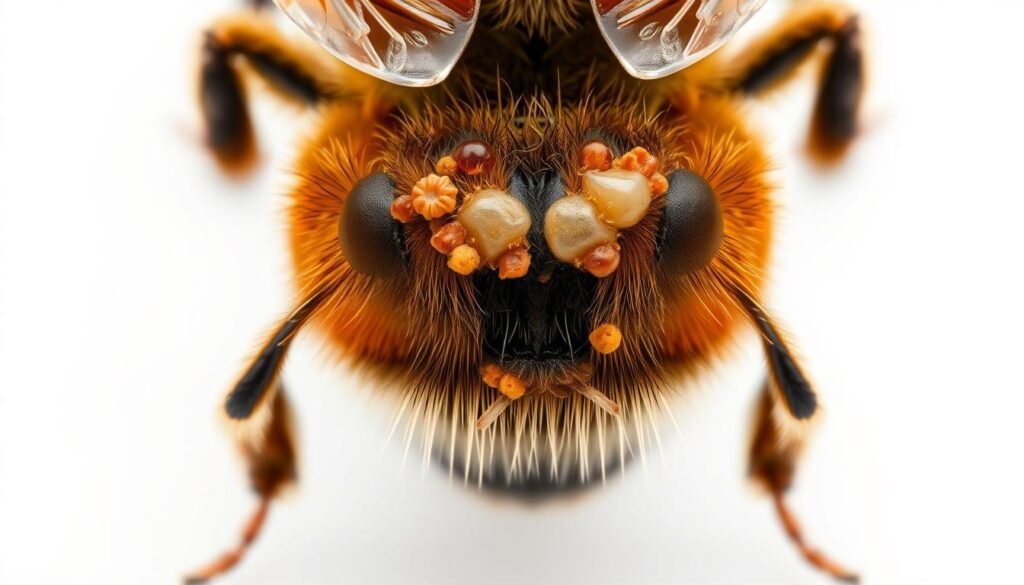

Look for mummies and fecal spotting at the entrance—these signs help separate fungal from gut infections early.

Chalkbrood: mummies and moisture stress

Chalkbrood infects very young larvae (about 1–4 days old). Infected larvae dry into white or black mummies that may be pushed out of cells.

Outbreaks often follow cool, wet spring weather and poor ventilation. Symptoms include punctured brood cappings and scattered mummies at the hive entrance.

Spores persist in wax, pollen, and honey for years, so sterilize or retire old comb to avoid repeat problems.

Nosema: oral-fecal spread and seasonality

Nosema apis and N. ceranae move via contaminated food and shared feeders.

N. apis often causes dysentery with pale or brown spotting at entrances. Infections peak from fall through winter into early spring when adult bees are confined and cannot defecate normally.

Fumagillin is not approved in the U.S., so management relies on sanitation, reduced comb transfers, and strengthening colonies with protein supplementation.

“Husbandry and clean equipment are the most reliable defenses against both chalkbrood and Nosema.”

- Improve hive ventilation and drainage to lower chalkbrood risk.

- Maintain strong colonies with adequate nutrition to resist microsporidian infections.

- Limit comb trading and sanitize gear; spores can survive long-term in hive products.

- Consider supportive compounds such as thymol and resveratrol, but prioritize husbandry and monitoring in spring.

| Infection | Key signs | Seasonality | Primary controls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chalkbrood (Ascosphaera apis) | White/black mummies; punctured cells; mummies at entrance | Often in wet spring | Ventilation, nutrition, hygienic stock, sterilize old comb |

| Nosema apis | Dysentery; fecal spotting at entrance; poor adult vigor | Peaks fall→winter→early spring | Sanitation, limit comb transfers, protein supplements |

| Nosema ceranae | Subtle decline; lower lifespan; weak foraging | Variable; can be year-round | Husbandry focus; consider thymol/resveratrol support; monitor |

Parasites and Pests That Drive Disease in Honey Bee Colonies

Pests that live on and inside adult workers or in brood cells are major drivers of secondary infections. Early detection and targeted control stop small problems from becoming colony-wide losses.

Varroa destructor: lifecycle and thresholds

Varroa destructor reproduce inside capped brood cells, feeding on fat bodies and vectoring viruses like DWV. Mite numbers often surge late summer as brood declines, so sustained suppression matters.

Integrated control combines labeled acaricides (amitraz, fluvalinate), organic acids and thymol, plus mechanical methods: drone brood removal, screened bottom boards, and timed brood breaks.

Tracheal mites and practical controls

Tracheal mites live in thoracic tracheae and are diagnosed by dissection of adult workers. Grease patties and menthol treatments help disrupt transfer to new bees and reduce infestations.

Small hive beetle and trapping strategies

Adults and larvae cause slimed comb and fermented honey. Use traps, oil cup traps, or baited cards placed out of reach of bees to protect stores without broad pesticides.

Greater wax moth: storage and biological options

Wax moth larvae damage weak hives and stored comb. Freeze comb, use Bt aizawai for stored frames, or keep colonies strong to prevent establishment.

“Pests stress brood and adults, and that stress opens the door to viruses and microbial problems.”

| Pest | Key sign | Primary control |

|---|---|---|

| Varroa destructor | Found in capped brood; mites on adults | Hard acaricides, oxalic/formic, drone brood removal |

| Tracheal mites | Respiratory decline; confirmed by dissection | Grease patties, menthol; requeen if needed |

| Small hive beetle | Larvae in comb; fermented slime in honey | Traps, oil cups, external bait cards |

| Greater wax moth | Chewed comb, tunnels in stored frames | Freeze or treat comb, Bt aizawai, maintain strong hives |

Integrated Pest Management for Lasting Colony Health

Integrated pest management (IPM) links regular monitoring, selective control, and nutrition to keep hives resilient. A clear, repeatable plan helps you act before a small problem becomes an expensive loss.

Monitoring and thresholds

Do biweekly checks in spring and fall to track mite counts and brood quality. Record the number of mites per sample and flag hives that exceed your action threshold.

Hard and soft treatments

Hard acaricides like amitraz and fluvalinate can cut high mite loads when used exactly per label. Soft options—formic, oxalic, and thymol—work well in specific temperatures and often during non-harvest periods to protect honey.

Mechanical and cultural tactics

Use drone brood removal, screened bottom boards, and planned brood breaks to reduce mite reproduction and lower reliance on chemicals. These measures help limit virus amplification inside a colony.

Nutritional support and records

Align protein feeding (pollen patties) with nectar flow to strengthen brood and larvae. Rotate treatments to slow resistance and keep standardized records for every hive to improve future control and treatment decisions.

“Pair chemical and mechanical tools, and document outcomes, to protect long-term colony viability.”

Seasonal Timing: Spring Build-Up, Summer Stress, and Winter Survival

Seasonal shifts set the pace for hive growth, stress, and the timing of key controls. Plan inspections and feeding to match spring brood surges, late-summer mite peaks, and the winter prep window.

Spring and early summer: brood surges, EFB, and sacbrood risk

Rapid brood expansion raises protein demand. Colonies under nutritional stress face higher risk of EFB and sacbrood virus in the first half of the season.

Action: check pollen stores, add supplements when needed, and keep brood compact to limit spotty patterns and weak larvae development.

Late summer and fall: Varroa peaks, DWV, and pre-winter treatments

Varroa often peaks late summer and drives amplification of wing virus and other viral problems. Treat mites before colonies make winter bees.

Schedule mite counts after honey removal so controls won’t contaminate honey and allow time for colonies to recover.

“Persistent spores and reservoirs can shape outcomes for years; sanitize equipment and manage stored comb carefully.”

Checklist for seasonal resilience:

- Inspect cells and capped brood for subtle symptoms during transitions.

- Monitor queen laying pattern; steady output supports winter survival.

- Align feeding and treatments with local nectar flows and weather.

| Season | Key risks | Primary actions |

|---|---|---|

| Spring–early summer | EFB, sacbrood virus, protein stress | Pollen supplementation, compact brood checks, prompt sampling |

| Late summer–fall | Varroa peak, DWV, weakened winter bees | Post-harvest mite assessment, timely treatments, requeen if needed |

| Year-round | Persistent spores, stored-comb reservoirs | Sanitize equipment, retire old comb, keep records |

Sanitation, Equipment, and Apiary Practices That Reduce Infections

Clean tools, scored woodware, and disciplined handling are the first line of defense against recurrent contamination in an apiary. A clear protocol reduces the chance that spores or residue move between hive locations.

Disinfection, frame management, and safe equipment reuse

Establish a sanitation baseline: disinfect hive tools and gloves between inspections and scorch or replace suspect wood boxes. Scoring or fresh paint on old wood helps identify used gear quickly.

Freeze stored comb to kill wax moth eggs and larvae before reuse. Consider Bt aizawai or approved storage chemicals where local rules allow, and always air equipment thoroughly before placing it in a hive.

- Segregate and label equipment by hive so frames and boxes are traced back if problems return.

- Retire frames with recurring contamination; inspect incoming frames for odd brood or larvae and for abnormal smells that may flag infection.

- Minimize frame swapping to avoid moving spores that can persist for years in honey and comb.

Limiting drift and robbing to prevent cross-colony infections

Configure the apiary to lower drift: stagger entrances, add landmarks, or vary box colors. These small changes reduce accidental movement of foragers between hives.

Manage robbing during dearth by reducing hive entrances and removing exposed honey. Disciplined hygiene and written sanitation logs improve trace‑back and lower overall disease pressure, reducing the need for harsher controls later.

“Consistent handling rules and careful equipment tracking are among the most effective steps a keeper can take to limit infection spread.”

Regulatory and Veterinary Considerations in the United States

Regulatory rules and veterinary oversight shape how treatments, reporting, and equipment sanitation are handled across U.S. apiaries. Under the Veterinary Feed Directive (VFD), access to antibiotics for american foulbrood and european foulbrood requires a veterinarian and proper documentation.

Many states require that american foulbrood be reported to the state apiarist. Officials may direct destruction of heavily infected hives, frames, and comb to halt spore spread.

When colonies are too weak or AFB shows resistance, burning or mandated disposal reduces long‑term risk. Salvageable woodware is often scorched and tools disinfected to lower residual bacterium and spores.

Always follow product labels for acaricides and other treatments used inside hives. Labels specify temperature windows, timing, and honey withdrawal periods that protect consumers and market access.

“Keep clear records of veterinary consultations, treatments applied, and affected hives to ensure traceability and regulatory compliance.”

Management of bee paralysis and paralysis virus revolves around vector control and husbandry. Chemical mite controls are regulated; use them per federal and state guidance to avoid contaminating honey.

| Action | Why it matters | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Report AFB | Stops spread to neighboring apiaries | State apiarist may order burning |

| Document VFD treatments | Ensures legal antibiotic use | Keep vet records with hive IDs |

| Follow label & withdrawal | Protects honey markets | Avoid treatments during honey flow |

Stay current with state rules on hive movement, cleaning standards, and permitted products. Good records and prompt vet contact protect your apiary and the broader community of honey bees.

Conclusion

A steady inspection routine turns small, fixable hive issues into manageable tasks instead of losses. Check brood, larvae, and adult bees with a clear checklist so you spot early symptoms fast and act before colonies weaken.

Combine sanitation, targeted pest control, and good nutrition as a unified strategy. Treat mites and virus risk ahead of winter, and use integrated tools rather than relying on a single fix.

Keep equipment clean, limit frame swaps, and reduce drift and robbing to stop spread between hives. Maintain records and regular sampling so each colony’s care fits its trends and risk profile.

Vigilance pays off: stay alert for pests in storage and weak hives, follow local rules, and pursue ongoing education. Disciplined practice protects honey yields and makes complex disease pressures manageable over time.

FAQ

What are normal brood patterns and how do healthy larvae look?

Healthy brood shows uniform capping and consistent age cohorts. Larvae are pearly white, C-shaped, and lie tightly in the cell. Spotty cappings, sunken cells, or discolored larvae indicate a problem that needs inspection.

How do queen, worker, and drone roles influence colony resilience?

A vigorous queen produces steady brood and maintains adult population; workers forage, nurse larvae, and groom pests; drones contribute only to mating. Strong task allocation and adequate worker numbers improve resistance to parasites like Varroa destructor and infections such as paenibacillus larvae.

How do infections spread through colonies and between hives?

Pathogens move via contaminated tools, robbing, drifting, and drifting foragers. Varroa mites vector viruses like deformed wing virus. Spores of American foulbrood persist on equipment and in honey, so hygiene and isolation are crucial.

What brood and adult signs should I watch for during inspections?

Check for sunken or perforated cappings, patchy brood, dead or trembling adults, hairless or deformed wings, and abnormal fecal staining. Presence of mummies, greasy or ropy larval remains, or spotty stores are red flags.

What simple field tests can help diagnose problems quickly?

The matchstick (ropy) test helps rule in American foulbrood when larval remains stretch. Visual sampling of frames, sticky board mite counts, and scheduled biweekly checks in spring and fall give early warnings.

How does deformed wing virus present and how is it linked to mites?

Infected adults show shrunken, crumpled wings and shortened abdomens. Varroa parasitism increases viral replication and transmission, so controlling mite levels lowers DWV impacts.

What are signs of acute or chronic paralysis viruses in adults?

Look for hairless, trembling bees, blackened bodies, and inability to fly. These viruses can cause rapid worker loss and reduced foraging, stressing the colony.

How does Israeli acute paralysis virus affect colonies?

IAPV can trigger sudden declines and poor foraging. Outbreaks often coincide with high Varroa pressure or nutritional stress. Rapid diagnosis and integrated control measures are essential to limit spread.

What does sacbrood virus look like in the hive and when is it common?

Infected larvae dry into canoe- or gondola-shaped scales that detach from cell walls. Spring brood surges and stressed colonies are most vulnerable; hygiene and reducing stressors help control it.

What are the hallmark symptoms of American foulbrood and how is it treated?

American foulbrood (Paenibacillus larvae) shows sunken, dark cappings and ropy larval remains. Spores persist for years. Many jurisdictions require destruction or sterilization of infected colonies and equipment; follow state regulations and consult a veterinarian or local extension.

How does European foulbrood differ and what management reduces its impact?

European foulbrood (Melissococcus plutonius) often arises in stressed or poorly fed colonies. Larvae may appear twisted or discolored but do not always show ropiness. Improve nutrition, reduce heat stress, and requeen if chronic.

What is chalkbrood and what conditions favor it?

Chalkbrood (Ascosphaera apis) produces hard, white mummified larvae in cells. High moisture and cooler broodnest conditions favor outbreaks. Improve ventilation, reduce humidity, and remove affected combs.

How do Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae present, and how are they managed?

Nosema causes dysentery, poor spring buildup, and reduced longevity. N. ceranae can be more chronic. Management includes good nutrition, replacing old comb, and approved treatments; monitor overwinter and in spring.

What are the key signs and thresholds for Varroa destructor?

Monitor using sugar shake, alcohol wash, or sticky boards. Treatment thresholds vary by season, but generally take action when mite levels exceed 2–3% of the adult population during brood rearing. Use integrated methods: chemical, mechanical, and cultural controls.

How are tracheal mites diagnosed and controlled?

Tracheal mites cause sluggish behavior and clustered bees. Diagnosis requires dissection or lab tests. Mechanical controls like grease patties, resistant stock, and brood management reduce impact.

What signs indicate small hive beetle infestation and how do I control them?

Look for tunneling in comb, slimy honey, and beetle larvae in brood areas. Use ground or trap-based controls, maintain strong colonies, and remove infested combs to reduce populations.

How do greater wax moths damage comb and how can beekeepers prevent losses?

Wax moth larvae tunnel through stored or weak comb, leaving webbing and frass. Prevent by storing frames cold or frozen, using sealed storage, and maintaining strong colonies to resist invasion.

What monitoring and IPM practices give the best long-term results?

Combine regular mite counts, biweekly checks in active seasons, drone brood removal, screened bottom boards, and timed chemical rotations. Balance “hard” acaricides like amitraz and fluvalinate with formic and oxalic acid treatments and cultural tactics.

When should I focus on nutrition and what supplements help?

Provide pollen substitutes or patties during dearths and early spring build-up. Ensure adequate nectar flow or sugar feed in late season. Proper protein balance and timely feeding reduce stress that predisposes colonies to infections.

How do seasonal dynamics affect disease risk across the year?

Spring brings brood surges and higher risk of EFB and sacbrood; late summer and fall see Varroa peaks and DWV amplification. Pre-winter treatments and mite control in late summer protect winter survival.

What sanitation and equipment practices reduce infection risk?

Regularly clean and disinfect feeders, hive tools, and frames. Burn or sufficiently heat-treat AFB-contaminated equipment per regulations. Limit drift and robbing by spacing hives and using entrance reducers.

What regulatory and veterinary considerations apply in the United States?

Reportable diseases like American foulbrood require notification and compliance with state apiculture laws. Work with state apiary inspectors, veterinarians, and extension services for diagnosis, permitted treatments, and disposal protocols.

How often should I sample hives and what should a sampling schedule include?

Sample at least biweekly during spring and fall mite pressure peaks, and monthly in stable summer periods. Include sticky board counts, brood inspections, and honey sampling when suspicious signs appear.

When is requeening recommended to improve colony health?

Requeen if productivity drops, brood patterns remain poor despite management, or temperament weakens. Replacing older queens often improves brood viability and disease resistance.

Which lab tests are best for confirming viral or bacterial infections?

PCR and culture methods confirm viruses and bacterial pathogens like Paenibacillus larvae or Melissococcus plutonius. Submit samples to university extension labs or accredited veterinary diagnostic labs for accurate results.

What personal protective and safety steps should be taken when handling infected hives?

Wear appropriate protective gear, minimize aerosolizing spores, and disinfect tools between hives. Follow local disposal rules for highly persistent pathogens and avoid sharing contaminated equipment.