Pollinators face deep risks as insect biodiversity has declined. Solitary species like Osmia bicornis play a vital role in crop and wild plant reproduction. Land-use change reduces flowers and nesting spots and alters the pools of environmental bacteria that offspring encounter.

This review outlines how pollen and ground materials supply microbes that shape larval nutrition, immune defense, and early development in trap-nesting megachilids. Field work in European grasslands and controlled model studies show that nest linings, provisions, and surrounding plants together form the microbial sources a young bee inherits.

We define the scope by comparing species with different nesting ecologies and by tracing which pathways respond to management. Pupae often reorganize their communities during metamorphosis, while larval guts and nest materials more closely mirror environmental variation.

The goal: map the major exposure routes, identify key pollen- and ground-associated bacteria, and show how farming choices shift these pathways over space and time. For background on factors that affect ground-nesting species, see this report on nesting sites and soil traits soil and nesting influences.

Key Takeaways

- Solitary bees provide essential pollination services and face pressure from land-use change.

- Pollen and ground materials act as primary bacterial sources for offspring.

- Nesting ecology and species traits modulate exposure routes and risks.

- Pupal microbiomes can reorganize during metamorphosis, differing from larval profiles.

- Microbial diversity supports ecosystem resilience and offers conservation levers.

Why bee-microbe ecology matters for ecosystems and agriculture

Microbial partners shape a bee’s nutrition, immunity, and ability to support plant reproduction. This link matters because declines in pollinator numbers can ripple through food systems and wild flora.

Pollination services, biodiversity, and the cost of decline

A single bee moves pollen among flowers and crops, boosting yield and stability. Microbiota improve digestion and pathogen resistance, so losing microbial diversity raises the real cost of decline biodiversity for farmers and natural areas.

From wild bees to Apis mellifera: shared functions, different risks

Wild bee species and managed Apis lineages both deliver pollination services, but exposure to agrochemicals, simplified floral resources, and altered soil pools varies. That creates distinct vulnerability profiles across species.

- Microbial buffering can reduce disease and help bees use varied diets.

- Habitat mosaics sustain floral and microbial reservoirs that keep pollination reliable.

- Climate shifts can desynchronize bee activity and flowering, compounding risks.

| Aspect | Wild bees | Managed Apis | Example impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foraging range | Often short | Varies with management | Local plant-pollen mix shifts |

| Exposure risk | High from habitat loss | High from agrochemicals | Microbial loss limits resilience |

| Microbial sources | Flowers, soil, nest materials | Apiary diet, floral patches | Nutrition and immunity altered |

“Microbiota can buffer a bee against pathogens and dietary variability.”

Conceptual framework: direct and indirect pathways linking bees, plants, soil, and microbes

A practical framework separates how nest materials and floral chemistry shape a bee’s microbial exposure.

Direct routes

Soil particles and nest partitions introduce environmental bacteria fungi into trap nests used by Osmia bicornis. Nest linings and mud walls carry microbes that can enter larval guts during feeding or cell maintenance.

Pollen provisions act as both food and an inoculum. Horizontally transmitted microbes in pollen supply a diverse microbial community that may aid digestion and defense.

Indirect routes

Plants influence microbial assembly through nutrient and chemical exchange. Floral chemistry and nectar metabolites select for taxa before a bee contacts them.

- Microbial growth in nests depends on moisture, substrate chemistry, and enclosure properties.

- Nesting choice and foraging portfolio predict exposure to particular taxa and functions.

- Management changes to floral and ground substrates should cascade into community shifts; these are testable predictions.

| Pathway | Vector | Effect on microbial community | Test metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct physical | Soil partitions, nest mud | Introduces environmental bacteria fungi to cells | Co-occurrence of taxa in soil and larval gut |

| Resource-mediated | Pollen provisions | Supplies inoculum and metabolites that aid digestion | Shared taxa across pollen and larvae; functional assays |

| Plant-mediated | Floral chemistry | Selects for taxa via nutrient/exchange filters | Correlation of floral metabolites with community composition |

“A framework linking nesting ecology with foraging predicts which taxa bees encounter and when.”

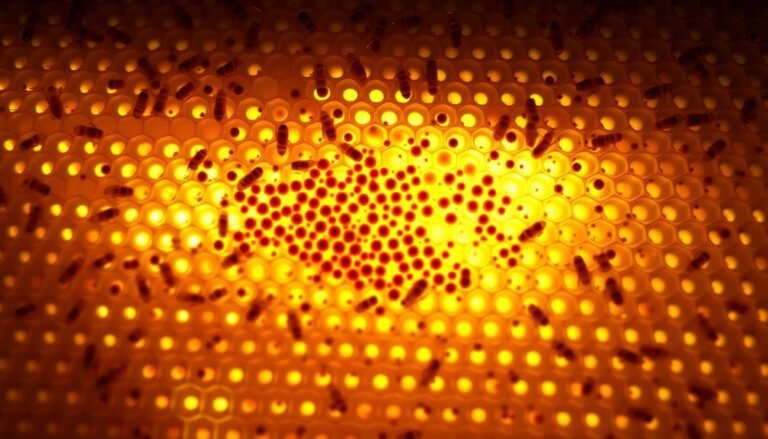

Evidence from solitary bee nests: bacterial diversity across pollen, soil, larvae, and pupae

A recent field study sampled Osmia bicornis nests across German grasslands to test how land-use affects microbial pools in nest materials and developing insects.

Observed patterns: Shannon diversity and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity

The study reported significant differences in Shannon diversity across four sample types: pollen provisions, soil nest enclosures, larval guts, and pupae.

With higher land-use intensity, Shannon diversity dropped in pollen, nest soil, and larval guts. Pupae showed little change, indicating resilience to landscape variation.

Bray-Curtis dissimilarity clearly separated pollen, soil, larvae, and pupae, showing distinct community composition per compartment.

Developmental reorganization: stable pupal microbiome versus variable larval gut

Results indicate larval guts track changes in nest materials, while pupae undergo community reorganization during metamorphosis.

- The soil enclosures and pollen provisions held overlapping but also distinct taxa, demonstrating the presence of environmental sources that reach larvae.

- Sample-type-specific indicator taxa were also observed, suggesting niche filtering within the nest microhabitats.

- Species-level signals appeared in some assays, but community-level patterns gave the most robust insight for management decisions.

Implications: these results support direct and indirect pathways from plants and soil into the larval microbiome. Targeting nest materials and provisions may help assess health risks or design beneficial inoculation strategies prior to the management-focused analysis in the next section.

Interactions between bees and soil microbes

Adult foraging and mud partitioning create predictable routes for environmental bacteria to reach offspring.

Nest architecture plays a key relationship role. Soil used as cell partitions can act as reservoirs of environmental bacteria. These reservoirs seed larval chambers during construction and maintenance.

Pollen provisions supply parallel inputs. Adults add pollen that carries its own microbiome, delivering nutrients and microbes that help colonize a young bee’s gut.

- Direct and indirect pathways: nest partitions introduce soil taxa while pollen brings floral taxa.

- Host filtering mechanisms then select which taxa persist during larval growth.

- Moisture and substrate chemistry modulate microbial growth and colonization success.

Species-specific nesting habits and local plants shape exposure profiles. Management at the habitat level can shift these inputs toward healthier microbiome outcomes.

“Nest materials and pollen jointly influence microbial succession from egg to larva and through metamorphosis.”

Land-use intensification as a driver of bee-associated microbial change

In landscapes with heavy management, reduced flower cover and simplified plant mixes change which bacteria reach nests. This study in German grasslands found that higher mowing, grazing, and fertilization levels correlated with lower Shannon diversity in pollen provisions, soil nest enclosures, and larval guts of Osmia bicornis.

Management gradients and microbial diversity loss

Frequent mowing and intensive grazing shorten bloom periods and reduce habitat structure. That limits pollen sources and shrinks the pool of floral and ground bacteria available to a bee.

Fertilization tends to homogenize plant communities. Fewer plant species mean fewer unique microbial associates reaching nests. The results show significant differences in microbial diversity across management gradients, consistent for nest materials and larval guts.

Resource-mediated effects on foraging and stress

Reduced floral diversity forces narrower diets and fewer beneficial microbes in provisions. That can increase physiological stress and lower digestive and immune support for young bees.

- Intensification exerts a direct impact on floral and ground resources, cutting microbial pool diversity.

- Resource-mediated effects propagate from landscape structure to nest microbiomes via altered foraging.

- Pupal stability suggests a developmental buffer, yet early stages remain vulnerable.

“Management choices at field and landscape scales can cascade into microbial diversity that supports bee health.”

Practical actions that restore plant diversity and soil quality offer a lever to rebuild microbial resources. For more on how habitat and soil traits affect nesting and resources, see this review on nesting sites and soil traits: nesting and soil influences.

Plant-soil microbe mutualisms that alter floral traits and pollinator attraction

Mutualisms between plants and beneficial soil bacteria can reshape floral form and reward, with clear consequences for pollinator behavior in nutrient-poor habitats.

Nitrogen-fixing rhizobia increase floral attractiveness in nutrient-poor soils.

Work with Chamaecrista latistipula shows that inoculation with rhizobia boosted plant growth in sandy, low-nutrient sites. Inoculated plants were taller and produced larger floral displays.

Rhizobia supply fixed nitrogen to the plant in exchange for carbon. That added nitrogen likely enhances pollen amino acids and protein, improving pollen nutritional quality. Anther reflectance patterns shifted in ways that matched Bombus female preferences for buzz-pollinated flowers.

Nitrogen fixation and Bombus visitation

Bombus, a genus of bumblebees, increased visitation to inoculated plants in nutrient-poor soil. The effect vanished in nutrient-rich soil, showing context dependence.

| Factor | Inoculated (nutrient-poor) | Control (nutrient-poor) | Ecological note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant growth | Higher | Lower | More floral display attracts more pollinators |

| Anther reflectance | Matched Bombus preference | Baseline | Visual cues drive buzz visitation |

| Pollen quality | Likely higher amino acids/protein | Lower | Benefits larval nutrition for a bee |

“Mutualistic bacteria can alter floral signals and rewards, increasing pollinator visitation where nutrients limit plant growth.”

- Evidence: plant-bacteria mutualisms can make flowers more flowers attractive to pollinators in poor soils.

- Mechanism: rhizobia fix nitrogen, boosting plant growth and possibly pollen nutrition.

- Pollinator response: Bombus females prefer altered anther reflectance and visit more often.

- Management: fostering beneficial soil bacteria offers a tool to improve resource quality for a bee and to support pollination services.

Honey bee gut microbiome insights: a model for host-microbe metabolic exchange

Research on the honey bee shows how host chemistry can feed specialized gut bacteria.

Snodgrassella alvi colonizes the honey bee gut by using host-derived organic acids such as citrate, glycerate, and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutarate. This uptake occurs independent of pollen or other microbes, highlighting a direct host-to-symbiont nutrient exchange.

Host-derived fuels and niche specialization

S. alvi converts kynurenine to anthranilate, modulating the tryptophan pathway and carving a narrow niche in Apis mellifera. That activity can shift host biochemistry and affect immune signaling.

Experimental evidence and methods

Researchers combined isotopic tracing, qPCR quantification, GC‑MS metabolite profiling, TEM imaging, and NanoSIMS to visualize metabolite transfer at cellular resolution.

- Model use: the honey bee illustrates how metabolic coupling supports gut microbiome stability.

- Implications: transformed nutrients may boost immune priming and gut barrier function in a bee.

- Contrast: soil exposure plays a smaller role here than in solitary species with environmental acquisition.

“Host-driven metabolite supply can secure symbiont colonization and function.”

These mechanistic findings suggest hypotheses for other species and point to lab methods—such as metabolite tracing methods—that clarify nutrient flows in gut microbiota studies.

Transmission routes: from flowers and soil to the bee gut microbiome

Larval exposure reflects the microbes carried on collected pollen and those stored in the mud partitions of sealed cells.

Pollen provisions as microbial vectors and external rumen

Pollen acts as both food and an external rumen that incubates fermentative taxa before larvae feed. These provision communities can change with floral diversity and bloom timing, shifting what a bee inherits.

Soil nest enclosures as reservoirs for environmental bacteria

Nest walls and mud partitions hold distinct soil-derived taxa that seed sealed chambers. Because maternal transfer stops once cells are sealed, local growth dynamics select which microbes persist during larval development.

Direct indirect routes contrast contact at flowers with selection inside nest cells. Flowers serve as microbial hubs for the plant community, while nest pools provide different selection pressures that shape gut assembly.

- Certain insects rely heavily on pollen-borne communities; floral loss narrows inputs.

- Soil disturbance alters the reservoir of environmental taxa available to nests.

- Compared to the honey bee model, solitary species show broader environmental acquisition and more variable trajectories.

“Sampling pollen, nest substrate, larvae, and pupae at matched time points is critical to infer directional transmission.”

Community structure and taxonomic signals in bee microbiota

Distinct microbial signatures form clear clusters when samples from provisions, nest walls, larvae, and pupae are compared.

The ordination plots from the study show reproducible grouping by sample type with significant differences in community composition. This pattern separates environmental sources from host-associated assemblages.

Certain higher-level taxa mark pollen versus nest partitions, while species-level resolution often depends on marker choice. Integrating plant species data refines which bacterial taxa are likely sourced from foraging.

Presence and relative abundance across compartments highlight candidate indicator taxa for monitoring environmental change. These signals also link composition to gut microbiome functions such as digestion and defense.

| Sample type | Typical markers | Functional hint | Management note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pollen provisions | Firmicutes, Actinobacteria | Fermentation, nutrient provisioning | Floral diversity predicts taxa |

| Nest partitions | Proteobacteria, soil-associated taxa | Environmental reservoir, inoculum | Substrate choice alters pool |

| Larval gut | Subset of pollen + host-selected taxa | Digestion and immune priming | Early diet shapes assembly |

| Pupae | Low diversity, reorganized taxa | Developmental buffering | Less responsive to landscape |

“Compositional patterns map onto function and ecology; nesting behavior and diet breadth shift taxonomic baselines.”

Methods matter: metabarcoding, bioinformatics, and statistics used in recent studies

Sequencing depth, primer choice, and contaminant control drive confidence in cross-compartment comparisons. A well-designed study used 16S rRNA V4 amplicons with dual indexing and PNA clamping to reduce chloroplast reads in pollen samples.

Pipeline details included VSEARCH merging, strict quality filters (Emax < 1), chimera removal, Unoise3 ASV inference, and SINTAX taxonomy against RDP v18. Selected ASVs were BLAST-confirmed at species rank when possible.

Analyses in R relied on phyloseq for data handling, vegan for NMDS ordination and PERMANOVA tests that detect significant differences, and mixed-effects models to estimate the direct impact of land-use while treating plot and region as random effects.

- Read-depth thresholds (≥1,000 reads) and negative controls reduced contaminants and improved inference.

- Method biases were also observed, such as residual organellar reads and taxonomic uncertainty.

- Integrating pollen, soil, and gut microbiota samples in one pipeline supports cross-compartment comparison and reproducible research.

“Transparent pipelines and rigorous controls are part of the toolkit needed for future multi-omic validation.”

Ecological outcomes: nutrition, immunity, and stress resilience in bees

Diverse microbial partners support larval metabolism, immune readiness, and steady growth in a bee. Early exposure from nest materials and provisions supplies functional taxa that aid digestion and nutrient extraction.

Functions such as fermentation and amino-acid provisioning can increase available nutrients and free essential compounds that promote faster growth. These metabolic services help larvae convert pollen into usable building blocks.

Microbial taxa also provide colonization resistance by occupying niches and producing antimicrobials. That lowers pathogen load and primes immune pathways, improving survival during vulnerable stages.

Land-use intensification reduced diversity in pollen provisions and soil inputs in the study. Reduced diversity can narrow dietary breadth and raise sensitivity to environmental stress.

Evidence shows that higher resource quality, including flowers attractive through plant-microbe mutualisms, indirectly boosts bee microbiota benefits. Host physiology then uses these microbial functions to maintain gut barrier integrity and modulate inflammation.

“Early-life microbial exposure sets a trajectory for resilience and health.”

- Manage habitats to increase pollen nutrient diversity and stabilize beneficial taxa.

- Monitor microbial metrics alongside nutrients and pathogens in health assessments.

- Prioritize early exposure windows to establish resilient communities in bees.

Cross-taxa synthesis: comparing solitary bees, Bombus, and Apis mellifera

Examining solitary, bumble, and honey systems clarifies which ecological levers shape microbial supply and persistence.

Shared functions such as nutrient processing and immune support appear across taxa, yet exposure pathways diverge with nesting ecology.

Shared functions, distinct exposure pathways

Solitary species acquire microbes largely from nest materials, pollen, and local soil. Maternal provisioning and nest walls shape early communities in these species.

Bombus respond to plant–microbe mutualisms: rhizobia-driven floral shifts can change foraging and nutrition for this genus.

In contrast, Apis mellifera shows strong host filtering. Honey bee gut symbionts like Snodgrassella alvi exploit host metabolites, creating stable niches in the honey bee gut.

- Solitary bee species: environmental acquisition via pollen and nest substrates.

- Bombus: foraging choices shift with plant species traits altered by soil mutualists.

- Honey bee: host-mediated colonization produces a resilient gut microbiome.

“Conservation must match interventions to life history: habitat and soil care for solitary species, colony and diet management for managed honey bees.”

This synthesis guides monitoring and taxon-specific risk assessments for U.S. landscapes, noting how bee species differ in exposure and microbiome assembly.

Management and conservation implications for U.S. landscapes

Simple, targeted management can reverse declines in floral and microbial resources that matter for bee health. Reducing intensification improves pollen variety and the microbial pools that reach nest materials and larval guts. These changes have a direct impact on early-life nutrition and resilience.

Enhancing floral and soil microbial diversity to support bee health

Diversify native flowering plants across seasons to expand pollen choices and maintain steady food supplies. Mix forbs, shrubs, and cover crops to provide continuous blooms and seed microbial reservoirs.

Practice soil stewardship: reduce tillage, add organic amendments, and limit broad-spectrum biocides to foster beneficial bacteria that improve plant traits and nest environments.

Reducing intensification pressures to mitigate microbiome dysbiosis

Lower mowing frequency, use targeted grazing, and restrain heavy fertilization to slow habitat simplification. These steps can increase floral richness and the biodiversity needed to buffer decline biodiversity effects.

“Targeted management has a direct impact on microbiome assembly in nest materials and larval guts.”

- Time mowing to avoid peak bloom and stagger cuts.

- Diversify hedgerows and field margins with native plants that make flowers attractive to pollinators.

- Monitor pollen and soil microbial diversity as leading indicators of habitat quality for different bee species.

Policy and practice should pair floral richness with microbial metrics in restoration, urban greenspace planning, and farm programs to protect bees at scale.

Key knowledge gaps and future research directions

We lack causal tests that link specific bacterial activities to host growth, immunity, and survival in a bee. Current evidence maps transmission routes and developmental reorganization, yet function and long-term outcomes remain unclear.

Priority research needs include longitudinal designs that follow microbiome assembly across developmental time and seasons. Experiments should move past composition to test which taxa or metabolites drive host benefits.

- Multi-omic studies that connect soil, plant species, pollen, and gut metabolomes in a unified exposure framework.

- Field trials as an example: habitat enhancements and targeted soil inoculants to measure measurable benefits in a bee.

- Long-term work on how climate extremes affect environmental pools and whether changes persist across generations.

- Evolutionary studies to test how nesting strategy and diet breadth shape resilience and assembly.

Methods and partnerships: standardize protocols, share repositories, and link ecologists, agronomists, and land managers to translate influence microbial processes into actionable conservation and policy. Future study designs should quantify the relationship of microbial signals to immunity and performance under realistic stressors.

Conclusion

Conclusions: Convergent evidence indicates that nest provisions and enclosure substrates are primary sources that set a developing bee’s microbiome trajectory.

Results show consistent declines in diversity across land-use gradients: pollen provisions and soil enclosures lose taxa in managed areas while pupae remain more stable. We also observed developmental buffering at the pupal stage, which highlights critical windows for action.

The study reaffirms the role of plant–soil mutualisms in improving floral traits and the value of honey bee models for metabolic insights. Practical steps include diversifying floral resources, restoring soil health, and aligning management with phenology and time-sensitive interventions.

Translating these findings into practice will help rebuild biodiversity and resilient pollination services for working landscapes. For guidance on habitat planning and climate-informed care, see beekeeping in different climates.

FAQ

What is the relationship between soil microbes and pollinators like Apis mellifera?

Soil microbes can colonize floral surfaces, nest material, and pollen provisions, providing a route for bacteria and fungi to reach pollinators. In Apis mellifera, some gut symbionts originate from environmental sources and then specialize, while others arrive via flowers or nest substrates and influence nutrition and immunity.

Why does bee–microbe ecology matter for ecosystems and agriculture?

Microbial communities linked to pollinators affect pollination efficiency, pollen nutrition, and disease resistance. Healthy microbial networks support plant reproduction and crop yields, while loss of microbial diversity can reduce pollination services and increase vulnerability to pathogens.

How do direct and indirect pathways link insects, plants, soil, and microbes?

Direct pathways include soil-derived bacteria and fungi entering nests or bee guts through contact with substrate and pollen. Indirect pathways act through plants: microbes alter nutrient uptake and floral chemistry, which changes nectar and pollen traits and thus the microbial and insect communities that interact with flowers.

What evidence exists from solitary bee nests about microbial diversity?

Studies comparing pollen, nest soil, larvae, and pupae show distinct bacterial communities across sample types. Metrics such as Shannon diversity and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity reveal higher variability in pollen and larval samples, with pupae often showing a more stable, reduced microbiome.

How does bee development affect microbiome composition?

Larval microbiota tend to be more variable and influenced by diet and pollen provisions. During metamorphosis, the microbiome reorganizes: pupae often host a simplified community with taxa adapted to the protected nest environment, while adults acquire additional microbes from flowers and social contact.

What are the impacts of land-use intensification on bee-associated microbial communities?

Practices such as frequent mowing, heavy grazing, and high fertilization reduce floral diversity and alter soil microbial pools. These management gradients often lead to lower microbial richness in pollen provisions and flower surfaces, increasing the risk of dysbiosis in pollinators.

How do plant–soil microbe mutualisms change floral traits and pollinator behavior?

Symbionts like nitrogen-fixing rhizobia can boost plant nutrient status, increasing floral size, nectar output, or pollen quality in nutrient-poor soils. These changes can raise visitation rates by Bombus and other wild bees and improve the nutritional profile of pollen for developing larvae.

What insights does the honey bee gut microbiome provide about host–microbe metabolic exchange?

The Apis mellifera gut harbors specialized taxa such as Snodgrassella alvi that metabolize host-derived compounds like organic acids. Microbial pathways, including tryptophan metabolism, illustrate niche specialization and coevolved functions important for host nutrition and immune modulation.

Through which routes do environmental microbes reach the bee gut?

Flowers act as key vectors: pollen provisions and nectar carry microbes that bees ingest. Soil around nests and nest linings also serve as reservoirs for environmental bacteria that transfer to brood cells and developing larvae.

Are there clear taxonomic signatures in bee-associated microbiota?

Yes. Certain bacterial genera recur across studies and host species, reflecting functional roles. Yet community composition varies by host species, nesting ecology, and local environment, producing taxonomic signals that align with ecological context.

What methods do researchers use to study these microbial communities?

Common approaches include 16S rRNA gene sequencing with PNA clamps to reduce host reads, ASV inference, and bioinformatic tools such as phyloseq. Statistical techniques like PERMANOVA, NMDS ordination, and mixed-effects models help test ecological hypotheses.

How do microbes influence bee nutrition, immunity, and stress resilience?

Microbial taxa can enhance digestion of pollen components, synthesize essential metabolites, and stimulate immune pathways. A balanced microbiome improves resilience to environmental stressors, whereas reduced diversity can impair nutrient uptake and increase disease susceptibility.

How do microbial communities compare across solitary bees, bumble bees, and honey bees?

All groups share functional microbes related to carbohydrate and amino-acid metabolism, but nesting ecology creates differences. Solitary species acquire more soil- and pollen-associated taxa, Bombus shows intermediate profiles, and Apis mellifera displays a more conserved social-gut community.

What management actions support healthy pollinator–microbe networks in U.S. landscapes?

Practices that increase floral diversity and reduce intensive mowing, overgrazing, and excessive fertilizer use help maintain diverse pollen and soil microbial pools. Restoring native plant communities and creating nest-friendly habitats conserve microbial resources that benefit pollinator health.

What are the major knowledge gaps and priorities for future research?

Key gaps include mechanistic links between specific microbes and pollinator fitness, long-term effects of land management on microbial transmission, and how climate change alters plant–microbe–pollinator networks. Standardized methods and longitudinal studies will improve causal inference.